Davidson’s Beginnings

In 1837 the Concord Presbytery founded Davidson College. These elders and pastors of the local area churches yearned to “bring the benefits of education within the reach of the poor boys of the community” (Shaw 11). Classes were predominately recitations in which students had to memorize and recite assigned readings regularly. Professors trusted their textbooks, seeing them as the definitive truth. They advised students against outside research, believing it would only confuse them (Blackstock). This style of teaching was consistent with other colleges, including Harvard, where the average student of the time would work from day to night completing prayers and recitations (Geiger, 53).

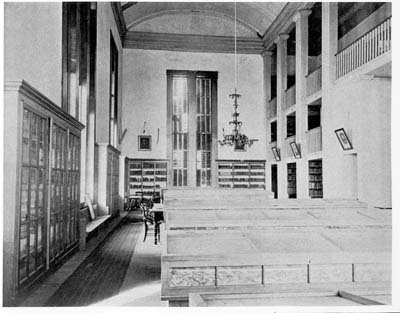

Chapel Library

In the early days of the college, there was no official library. Instead, the faculty oversaw a collection of 350 educational books in the Chapel, one of the oldest buildings on campus. The College purchased only a small amount of these works, the rest were donations from members of the community.

No form of organization existed in its stacks; no librarian was hired to keep order. Its book selection was limited to texts of theology and the English translations of Greek and Latin literature. The magazine collection held publications including: “New Monthly Magazine”, “Church History”, and “Medical Recorder” (Library Catalog of 1841). To call this room a library was to give it more credit than it deserved.

The Introduction of Literary Societies

Soon after Davidson was established, students created two Literary Societies for social and intellectual stimulation. The Philanthropic Society and the Polemic Debating Society (changed to the Eumanean Society in 1838) were created for “the study of rhetoric, logic, and ethics [with] a high regard for virtue and truth.” (Blackstock) Although the Phi and Eu Societies desired to be different from one another, their practices were nearly identical. Each stated the same overall objective of seeking “improvement not to be secured in the regular college work.” The societies established a framework of rules that structured weekly meetings. These meetings were held in the basement of Davidson’s chapel until 1849 and 1850, when the building of the Phi and Eu halls was completed (Beaty 42-46).

The society members submitted papers, prepared speeches, and read debates, all of which coincided with the topic of the week. Interests ranged from “Is female education of as much importance as male education?” to “Has a state the right to secede from the union?” allowing students to investigate all facets of life (Beaty 43). According to Roger L. Geiger in The American College in the Nineteenth Century, through discussion in the literary societies students were able to shape “an education that they considered relevant to their future lives” (14). While students respected their classical training in the classroom, they joined literary societies to expand their education.

Within the societies students conducted original research, rather than simply absorbing what their professors explained. To complement this independent search for knowledge, the greatest asset of both Phi and Eu Societies were the libraries that made their objectives a reality.

The Society Libraries

The libraries were the cornerstone of both the Phi and Eu Societies. Members used their respective libraries for research, and to prepare speeches, debates, and essays for upcoming meetings.

Throughout Phi Society minutes note that members’ fees were mostly spent on purchasing new books and ensuring that old books were kept in good condition. They also mention a contest, in which, whoever donated the most books to the society received a prize. In one case, a nonmember donated over thirty volumes, but did not win because only members of the Phi society could.

Most importantly, because the books were used for reference in debates and speeches, they were for the specific society’s eyes only. Any student that was not a member of a particular society did not have access to the documents; even faculty members had to follow this strict code.

Although the societies were thriving in their efforts to collect literature, they eventually ran out of space and money. Both societies were over $1,000 in debt after constructing their halls (Beaty, 47). Alberto Manguel analyzed spacial limitations in The Library at Night, claiming that “the problem of space is inherent in any collection of books” and libraries must resort to “painful devices” such as “pruning their treasures [and] giving away their paperbacks” in order to control the surplus of books (Manguel 66). The societies cared too much for their books to simply throw them out, but lacked the funds to create their own libraries separate from their respective halls.

They needed a solution that allowed them to keep their books while also making room for more. This solution was the Union Library.

Chambers Library

Old Chambers was built in 1860, and it contained a library on the south-west side of the second floor. Although the library was brand new, the faults found in the Chapel Library were not much improved. The books were simply transferred from the Chapel Library to the Old Chambers Library, which also lacked any heating for the cold winters or light during the dark hours of the night (Erwin).

The Creation of the Union Library

As the professors realized the lack of books in the Chambers Library to be a significant problem, they urged the literary societies to consolidate their libraries. Simultaneously, the societies were running out of space for their growing collection of books. After many debates, lectures, and committee meetings, both societies agreed to donate their books to the Old Chambers library renaming it “The Union Library” because of the merging of the Phi and Eu society libraries.

The Development of the Union Library

Although the societies were giving up their books, they did not plan to give up the rules that kept their libraries in such pristine condition. The diplomatic nature of the students and the faculty led to the establishment of a Library Committee, with two students from the Phi Society, two from the Eu Society, and one faculty member at its head. This committee was expanded to add professional librarian Cornelia Shaw when she was hired by the college in 1907. According to the Union Library By-Laws (1887), the committee was in charge of “receiving all moneys” and “purchasing books, papers, periodicals, etc.” (“Regulations for the Management of the Union Library of Davidson College” 37-38). The members of the committee met twice a week and had strict orders to give a report to their respective societies.

As space continued to become an issue for the Union Library the College sought to find an independent building to act as Davidson’s definitive library. Thus in 1910 the Carnegie Library opened and the majors texts from the Union Library were transferred to this new location. A library space still remained in Old Chambers. It acted as a complementary library to Carnegie, albeit a very insignificant one. It remained open two hours a day in the afternoon (Erwin) and housed around 7,000 old books, mainly government volumes (Shaw 92).

For over a decade, this library remained a study spot for the students of Davidson until a fire razed Old Chambers on November 21, 1921 and brought an end to the space that saw the beginnings of the Union Library. The loss of this original library was relatively insignificant, however. Cornelia Shaw stated in a letter to her colleague in 1921, how few books were lost and gave no remark of possibly replacing the history that burned away. Although the fire marked the end of the Union Library, the legacy of student involvement in the library remains.

Conclusion

The Union Library represented not only the introduction of a formal library to Davidson, it was also a primary example of student initiative. If it was not for the existing libraries of the Phi and Eu Societies, the Union Library would have never come to fruition. As Davidson’s E.H. Little Library now stands 600,000 volumes strong, remember that its origins came from students who built their own original libraries.

Davidson College. Quips and Cranks Vol. 1. Davidson: Davidson College, 1895.

Erwin, E.J. “Snapshots of Half Century at Davidson.” Quips and Cranks. Davidson: Davidson College, 1950.

Shaw, Cornelia Rebekah. Davidson College; Intimate Facts,. New York: Fleming Revell, 1923.

____ Letter to Mr. Harper. November 28th, 1921. RG 3/4 Library. Davidson College Archives.

Cite as: DeSimone, Michael and Kristy Helscel, Sarah Kim and Louise Tiller, “Union Library,” Davidson Encyclopedia, October 2011, <https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/archives/encyclopedia/union-library/ >

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.