In Fall 2019, Archives, Special Collections, & Community (ASCC) had the privilege of working with Dr. Rose Stremlau’s “HIS 306: Women and Gender in U.S. History to 1870” course. Over the course of a semester, students researched the history of women and gender in the greater Davidson, North Carolina area using materials in the Davidson College Archives and other local organizations. The following series of blog posts highlights aspects of their research process.

Written by Tracey Hagan, a student-athlete senior psychology major from Ridgefield, CT. Student in History 306: Women and Gender in US History from to 1870.

Davidson College Presbyterian Church (DCPC) began as a small congregation of six women, two male elders, Robert Hall Morrison as the leader, and fifteen Davidson students in 1837.1 As the Church grew, it became more than just a place for worship. The Church developed into a social institution for its members, specifically for the women of the church.

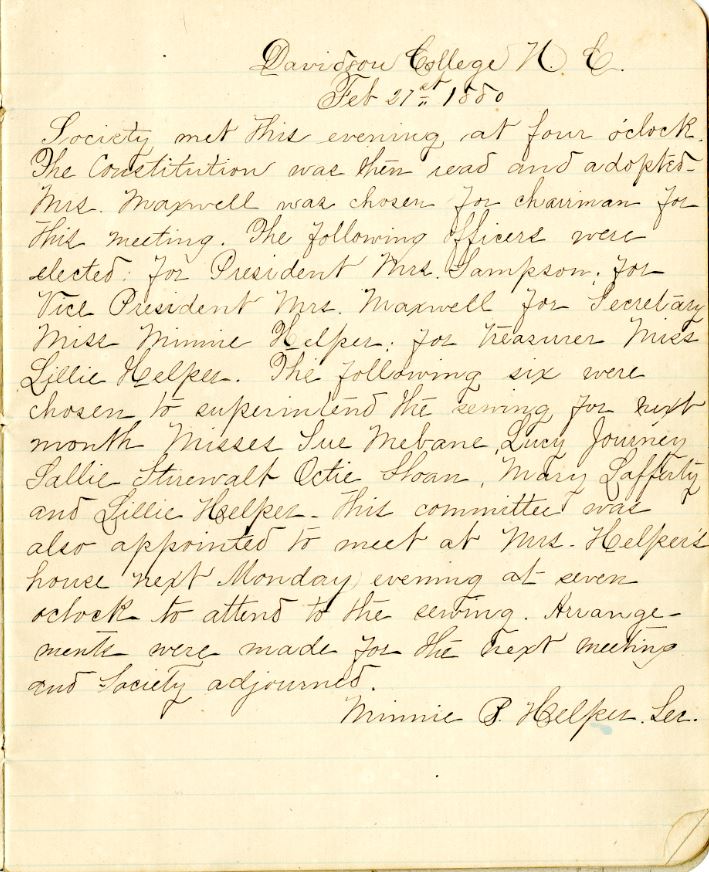

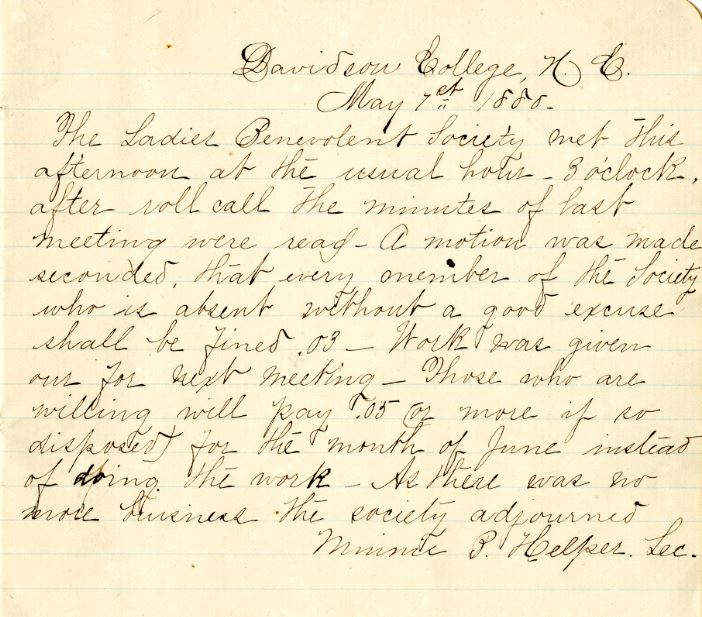

The Ladies Missionary Society Constitution was created in 1885. In its first year, Mrs. Dupuy was nominated president, Mrs. Knox was vice president, and Mrs. Vinson was secretary. The constitution contains a preamble and twelve articles. The articles provide the details about what was to happen at each meeting of the society. According to the constitution, they were to meet at a minimum on a monthly basis to discuss selected articles about other missionary works in America, Asia, and Europe or Africa. Generally, the meetings consisted of attendance, reading, singing, general business discussion, and the president’s appointment of the readers for the next meeting.

This three-page constitution alone shows that the white women of Davidson in 1885 had a much more hands on role in DCPC than what was expected from the Presbyterian Church norms of that era. Women’s roles in the Presbyterian Church in general were limited to leading Sunday schools, attracting new members, running women’s prayer meetings and church organizations, furnishing the church and raising her own family.2 Women were not to be active members in the church, or hold any leadership positions.3 Despite the General Assembly’s restrictions on women’s roles within the church, the Davidson women formed this society.

They wrote the constitution and ran this entire group on their own. In this way, this society gave them a position of power outside of the traditional roles and domestic sphere to which the Church and societal traditions confined them. The society also served as a form of group education. The members were essentially given homework assignments to learn about other missionary works across the country, and across continents. In this way, this society served to empower its members. It is important to note that not all the women of the town were members. As outlined article 8 in the constitution, members were strongly encouraged to give monthly donations to the society. This monetary element of the society may have made it so only affluent white women in Davidson could be members. While this society certainly gave white women in Davidson some more power in their lives, it did not extend this opportunity to all the women of the town.

Works Cited:

[1] Beaty, Mary D. A History of the Davidson College Presbyterian Church . Davidson College Presbyterian Church, n.d.

[2] Boyd, Lois A. “Presbyterian Ministers’ Wives—A Nineteenth-Century Portrait.” Journal of Presbyterian History (1962-1985) 59, no. 1 (1981): 3-17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23328155.

[3] Brackenridge, R. Douglas, and Lois A. Boyd. “United Presbyterian Policy on Women and the Church—an Historical Overview.” Journal of Presbyterian History (1962-1985) 59, no. 3 (1981): 383-407. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23328186.