The Library’s department Discovery Systems is changing names to Library Technologies and Metadata. It seems the idea of a library is well ingrained in our social fabric. With that as part of the name, people know we are talking about information, research, description, access, and sharing. Without library in our name, people wonder what Discovery and Systems might be about. Well, certainly discovery of desired information is one of the goals of the library’s services. So is discovery of the unknown. Discovery is one objective of technologies used in the library. Accounting and notification are others. Digitization, security, access, cooperation, problem solving, and consistency – these are more goals of the technologies managed by the library.

Perl script to convert catalog record to a spreadsheet

The Systems Librarian Susan Kerr works with equipment, installations, applications, and databases that support the services of the library. As the landscape shifts, new tools are adopted and data is converted. Systems involves administering these applications and applying technical skill for data creation, manipulation, and access.

The Cataloging and Metadata Librarian Kim Sanderson works to organize and describe library collections so that the library remains the place for discovery. This year, the Library Technologies and Metadata department will describe our work in more detail, beginning with Metadata.

METADATA: a brief introduction

A brief definition of metadata is data about data. The actual word ‘metadata’ was first used around 1970, but metadata has been used in libraries in the card catalog since the mid-18th century. The information on the cards is now in electronic format, but still contains the same various kinds of metadata. This metadata is used by library patrons to identify and locate resources and also serves as an inventory of a collection.

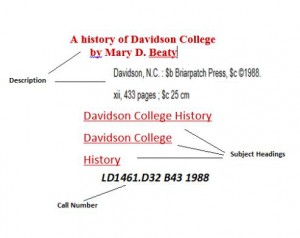

Metadata of the book, A History of Davidson College by Mary D. Beaty

The main body of the data is called descriptive cataloging. This data consists minimally of title, author, publisher, place of publication, and year of publication. For items published after 1966 there is an ISBN, a unique identifier. Also recorded is the number of pages, any illustrative matter, and the size of the book from top to bottom in centimeters. Most library users would only be interested in the author/title information, but the rest of the description is invaluable to catalogers. All of this data is transcribed according to rules in a particular format. By looking at the descriptive cataloging, a cataloger can determine if a record for a title in hand is the correct one in the WorldCat database, which currently has almost one billion records. If one does not exist, one must be created.

Then there are the subject headings. There are over 330,000 names, places, and topical subject headings used by the Library of Congress. Added to those are thousands of subheadings to add specificity. The subject headings have been authorized so that they are consistent. One heading can be used to find other titles with the same heading. Subject analysis is the most difficult task in cataloging. Distilling the contents of a resource into a handful of terms without actually reading an entire book, which is sometimes about an unfamiliar subject or in a different language, can be challenging.

A finding aid in conjunction with subject headings is the call number. This not only serves as an address as to where to find the physical item, but also works to bring like items together. The call number consists of a classification number, a cutter number which is usually derived from the authors name or title of the book, and the year of publication. Since 2008? use the classification created by the Library of Congress (LC) and are in the process of converting our Dewey Decimal collection to LC.

More data about LT&M to come…