Introducing guest blogger Hannah Foltz ’13! Look forward to additional posts this summer!

Hello! I’m Hannah Foltz, class of 2013 and current PhD student in rhetoric at the University of Texas at Austin. This summer, I’m working with the Humanities program and the Archives and Special Collections team. I’ll be scouring the College’s archives, documenting and studying depictions and erasures of marginalized populations in historical materials. Because of my disciplinary background, I am most interested in the archives’ rhetorical role, or in other terms, how the records and materials we deem worthy of saving work to define the im/possibilities of not only historiography, but also of popular conceptions of identity and belonging.

This week, I’ve been working my way through Quips and Cranks, the College’s yearbook. One of the volumes’ most popular tropes is that of the “Davidson Spirit.” Year in and year out, it is heralded as that je-ne-sais-quoi that makes Davidson a special place. Even today, College marketing centers on the notion of being “Distinctly Davidson.”

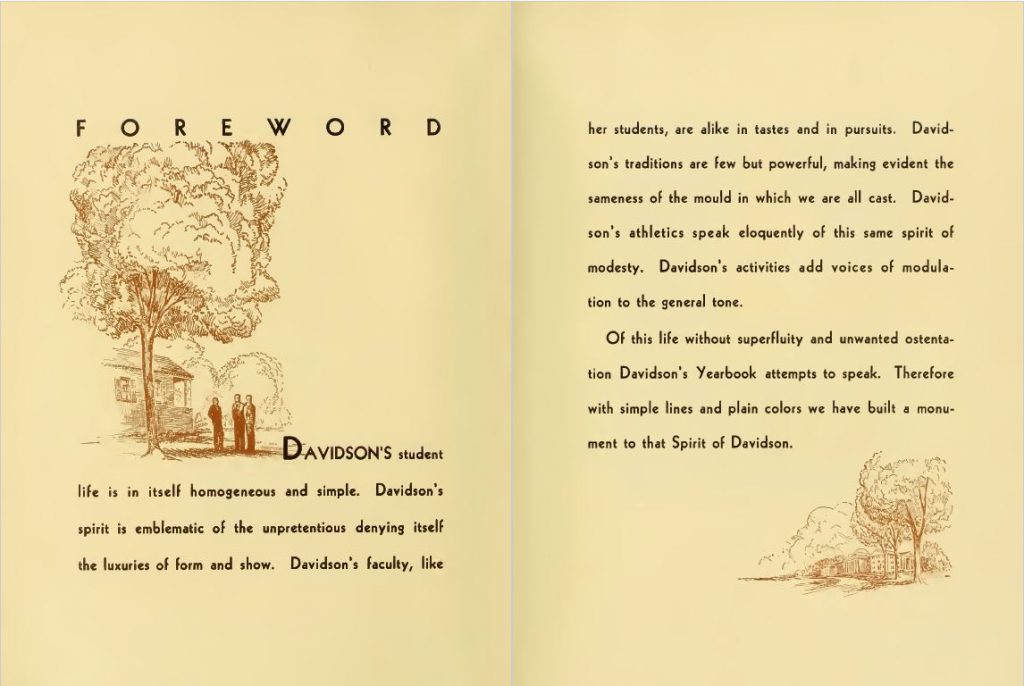

But what does it mean to possess the “Davidson Spirit?” I was struck by the evolution of this concept, which is illustrated by contrasting the Forewords of Quips & Cranks from 1933 and 1952.

“Davidson’s student life is in itself homogeneous and simple. Davidson’s spirit is emblematic of the unpretentious denying itself the luxuries of form and show. Davidson’s faculty, like her students, are alike in tastes and pursuits. Davidson’s traditions are few but powerful, making evident the sameness of the mould in which we are all cast. Davidson’s athletics speak eloquently of this same spirit of modesty. Davidson’s activities add voices of modulation to the general tone.

Of this life without superfulity and unwanted ostentation Davidson’s Yearbook attempts to speak. Therefore with simple lines and plain colors we have built a monument to that Spirit of Davidson.”

1933 (Robert L. McCallie, ed.)

“Every man in the class is different. Everything we do is unique. We are a class and as a group we have characteristics that are solely our own. We have lived together and suffered together and out of this heroic mixture we have developed a sense of brotherhood that makes us distinct from any other class before and since…

The Davidson Story is not devoted to any one class or any one group of any description. It is a blend, whether good or bad, of the character of anyone that has ever participated in the corporate life that is the college. From the President to the rawest janitor, each has a role and a line in the comedy or the tragedy that is Davidson.”

1952 ( William A. Adams, ed.)

While perhaps the dourness of 1933 can be attributed to Depression-era values or a reaction against rising fascism abroad, it’s clear that its notion of the Davidson Spirit is one that is static and inherent. It is something one is born with, something that determines membership in the community. It is very Protestant. It is a “sameness of mould.”

Fortunately, by 1952, the notion of the Davidson Spirit (or Story, in this case) had grown closer to how we conceive of it today: an ethos developed through a shared transformative experience, not through any inherent sameness. This Spirit can be taken up by every member of the community, each in his own way. This Spirit includes a recognition of the good—and the bad—in its past and present. All in all, where the other is unchangeable and exclusive, this Spirit is dynamic and welcoming.

Yes, Davidson was still far from realizing this ideal Spirit in 1952; it was still all male, and virtually all white and all Christian. And yet, this articulation of an alternative kind of unity marks an important step towards building the kind of inclusive, generous, and enjoyable educational community we are still striving to create.