Home — 1837-1865 — 1865-1900 — 1901-1962 — 1962-Present

The question of race relations moved from day to day interactions into the chapel and publications where students began to here more lectures and write more articles. In 1901 Reverend Mr. Lily, evangelist of colored work in Alabama, gave us a very instructive talk on the duty of the church toward the negro. He pointed out the natural deficiencies of the Negro, and indicated the way to meet them. In 1918, Reverend John Little gave a lecture on the “The Negro Problem” inspiring enough that a canvass of the student body was made and seventy new men signed up for an ongoing study of” the negro problem.”

Even as race was being treated as an intellectual and religious concern, students opened their ears to African-American entertainers. Student singers from historically black colleges including nearby Johnson C. Smith made regular and popular visits to campus and students took trips into Charlotte to hear nationally known performers such as the Mills brothers. By the 1950s, black performers appeared regularly on campus, Louis Armstrong playing here 3 times, and in 1961 Otis Reading played an early concert here.

Students also periodically expressed interest in the lives of college workers, writing sketches for the Davidsonian that reflect a mix of paternalism and respect. A 1926 article describes Baxter Williamson, who began working for the college at age 14 and was still working 56 years later. “At the time of his birth his mother was a slave and he himself was owned by ‘Little John’ Patterson… All of his life has been spent within a radius of a few miles of Davidson. He still acts in the capacity of a janitor, his main duty being to bring the mail to the offices. He carries a small mail bag and wears a white coat with DC stamped on it.”

Students also periodically expressed interest in the lives of college workers, writing sketches for the Davidsonian that reflect a mix of paternalism and respect. A 1926 article describes Baxter Williamson, who began working for the college at age 14 and was still working 56 years later. “At the time of his birth his mother was a slave and he himself was owned by ‘Little John’ Patterson… All of his life has been spent within a radius of a few miles of Davidson. He still acts in the capacity of a janitor, his main duty being to bring the mail to the offices. He carries a small mail bag and wears a white coat with DC stamped on it.”

According to a 1936 Davidsonian article, “Colored people are almost always interesting, and the Davidson janitors are no exception. They range in length of service from Enoch, who claims to have been here when Dr. C. R. Harding first came (1888) to the men who have been put on in the last year or two . . . Wesley is Mrs. Smith’s right hand man. She describes him as a ‘good negro executive’ and he also has quite a reputation as a churchman.”

Along with the occasional article on staff, student groups, particularly the YMCA developed service projects in the African-American community including tutoring, sponsoring boy scout troops, developing sports programs and even building a community center and teaching adult education classes.

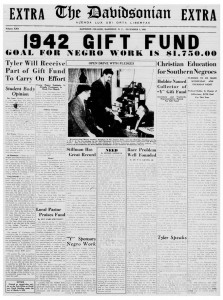

Still in 1942 the decision to direct the YMCA gift fund toward negro education was a controversial issue. One Y leader wrote: “Speaking quite frankly, the Cabinet does not anticipate that the project for this year will meet with unanimous approval on all sides. Davidson would have to be too unlike its environment for that to happen. But in a real sense, the fact that this is a controversial issue is all the more reason for bringing it to the front.” The entire front page of the December 7, 1942 Davidsonian addressed the gift fund and race issues.

Despite continued segregation and awareness of the reluctance of both students and administration to support substantial social change, dining service employees jointly contributed to the college’s fundraising campaign and presented a check to President Cunningham.

The 1950s brought more calls for change, stimulated in part by a fire off Main Street in Davidson in Brady’s alley – home to a number of African-American families.  The fire prompted the town and college community to work on better housing for local families. The YMCA continued to lead in the area of race relations creating opportunities for interaction and discussion.

The fire prompted the town and college community to work on better housing for local families. The YMCA continued to lead in the area of race relations creating opportunities for interaction and discussion.

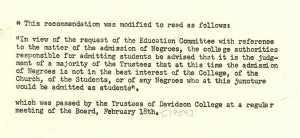

With the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling in 1954, questions of integration became more pronounced. In 1959, the college issued an official statement:  In view of the request of the Education Committee with reference to the matter of the admission of Negroes, the college authorities responsible for admitting students be advised that it is the judgment of a majority of the trustees that at this time the admission of Negroes is not in the best interest of the College, of the Church, of the Students, or of any Negroes who at this juncture would be admitted as students.

In view of the request of the Education Committee with reference to the matter of the admission of Negroes, the college authorities responsible for admitting students be advised that it is the judgment of a majority of the trustees that at this time the admission of Negroes is not in the best interest of the College, of the Church, of the Students, or of any Negroes who at this juncture would be admitted as students.

Student opinions were slowly shifting, with more voices speaking for change. Alumni were even more active, particularly those involved with the Board of World Missions of the Presbyterian Church. Thus, the 1959 decision was reversed within 2 years, as the Trustees voted in February 1961 to admit African students – that is, international students from the Congo. Ben Nzengu broke Davidson’ color all when he entered in the fall of 1962. He was joined by Georges Nzongola in 1963.

The trustee decision in 1961 was not welcomed by all. Students involved in local sit-ins found themselves ostracized by other students and local merchants resisted changing any segregation practices, even for international students of color. The spring before Ben entered Davidson, only 53% of the students supported integration of the college – but more local merchants were willing to serve students of color.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.