Hello, this is Ghadeer Muhammed ‘25, and I hail from Cairo, Egypt. This summer, I worked in the Archives, Special Collections and Community department, and I have stumbled upon a most interesting diploma collection. Allow me to offer you a peek into the Archives diploma collection, and the college history it unveils…

The Davidson College Archives has acquired 41 diplomas solely through donations. The collection houses diplomas issued from 1840 to 2008. 19 diplomas, which is about half of the diplomas in the collection, date back to the 1800s, while 20 diplomas, the other half, were issued in the 20th century. The remaining two diplomas in the collection are dated 2006 and 2008.

40 of 41 diplomas in the collection belong to male Davidson College students, while one out of 41 diplomas belongs to a female Davidson College student. This is noteworthy and timely, as 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the official formal admission of women to Davidson College (1972) thus ending the all-male aspect of the institution.

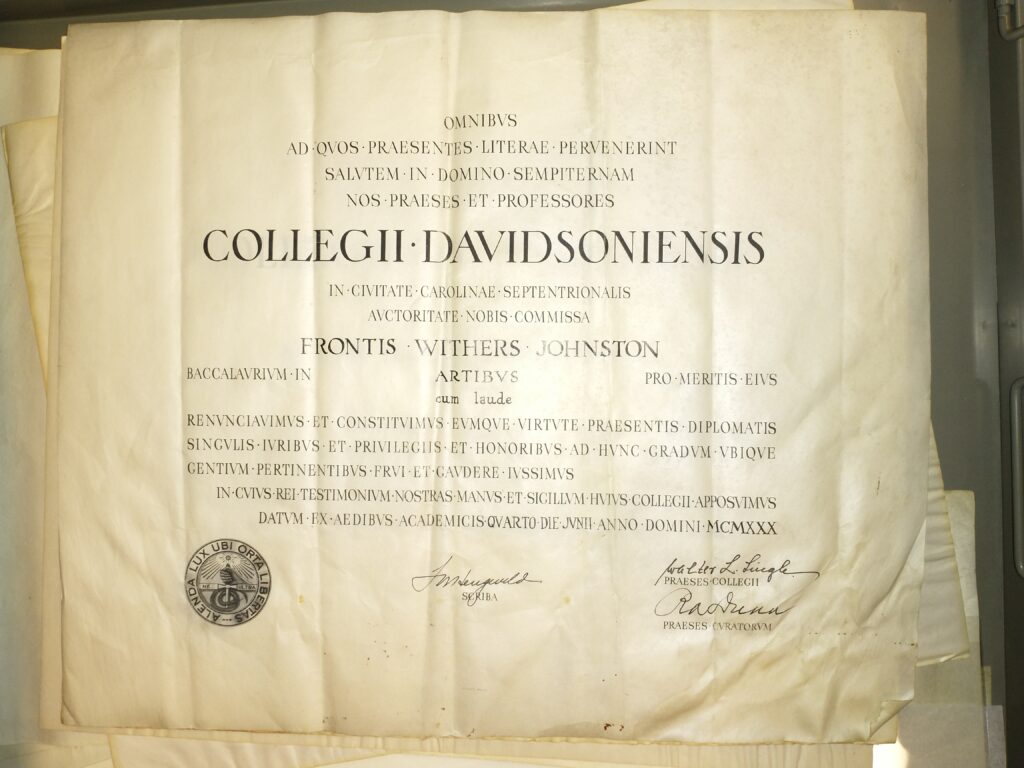

The overwhelming majority of the diplomas in the collection are made of vellum – more accurately described as sturdy sheepskin. Before 1981, all Davidson College alumni received their diplomas made of vellum. In 1981, parchment diplomas became the default, but students could still request a diploma made from sheepskin at a $10 charge. The complete switch to parchment diplomas was not put into action by the Registrar until the beginning of the 21st century. So for 141 years, Davidson College used vellum to award all alumni their graduation diplomas. Furthermore, the language used in all Bachelor of Arts diplomas, 19th and 20th centuries, is Latin, and even the date is in Roman numerals. However, from 1870-1889 the Bachelor of Science diploma was issued in English. Today, The Davidson College Registrar issues graduation diplomas in Latin.

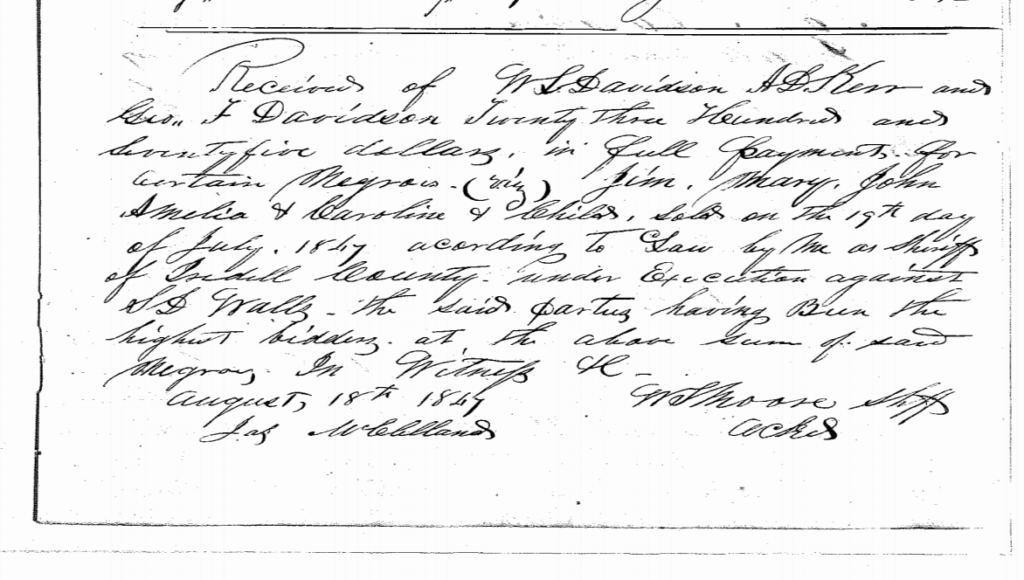

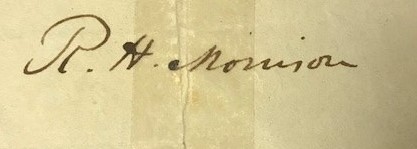

Each diploma is signed by the sitting College President and on some occasions, the Board of Trustees too. The earliest diploma in the collection is dated 1840 and was signed by Robert Hall Morrison, the first president of Davidson College.

One truly interesting aspect of working in the archives is witnessing the passage of time and the related parallelism of events. A fine example of this parallelism is the journey of Walter Lee Lingle back to Davidson College. The Davidson College Archives has two diplomas dated 1892 and 1893 for a certain Walter Lee Lingle. This alumnus returned to Davidson College in 1906, but this time as the eleventh president of the college. Consequently, today, the archives diploma collection holds a 1930 Bachelor of Arts diploma signed by Walter Lee Lingle as President.

Lingle was the third Davidson College President who was also a Davidson College alumnus. Alumni presidents are not uncommon in Davidson College as the current president, Douglas Allan Hicks, is the eleventh alumni president in the history of the college.

References

Blodgett, J. 2011 Davidson College Diplomas – Davidson College Archives & Special Collections. https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/archives/encyclopedia/diploma

Blodgett, J. 2011 Lingle, Walter Lee – Davidson College Archives & Special Collections https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/archives/encyclopedia/walter-lee-lingle

Johnson, M 2022 Douglas A. Hicks selected as 19th president of Davidson College https://www.davidson.edu/news/2022/04/29/douglas-hicks-selected-19th-president-davidson-college#:~:text=Davidson%20College%20Trustees%20today%20unanimously,returns%20to%20where%20it%20began.