Hello everyone! Andrés Paz ‘21, current JEC Fellow here. As the days get colder and we switch our attires to warmer ones, I figured it would not be a bad idea to talk about some of the early days of Davidson. Why not grab a warm drink and let me tell you a bit about how it looks to research about Davidson as part of the Archives, Special Collections and Community team?

Before anything, it is relevant to say that some of the sources I touch upon depict racist, discriminatory, or violent language and/or actions. This content can be distressing. It is also helpful to acknowledge that the life of individuals and communities in the past was as complex as we can feel ours to be now. For this reason, much of what I share will be incomplete, but hopefully encourages at least someone to keep reflecting on the meaning of living, working, studying, and just being around Davidson.

As we become increasingly interested in certain aspects of Davidson’s past, figuring out how to present a somewhat complete narrative of anything tends to be a hard task, particularly because official records and archives can, in subtle and overt ways, silence the lives and actions of certain groups: enslaved people, women, and children are important examples. As we grapple with such circumstances, it is too easy to write yet another narrative about powerful, influential white men. More important, however, is simply to abstain from grandiose stories of great men who had virtually no flaws. As I just said, we know life is more complex than that!

So, how can it look to do research about Davidson as part of the ASCC team? Let me answer that by (re)telling fragments of a story, which is perhaps more a compendium of facts and half-facts difficult to corroborate that can begin in many places… in the same way that your own research about a person, place, or event could do!

In its early days, Davidson College opened its doors to young men that came mostly from North and South Carolina. Many of them, as in the case of Dr. James Hiram Houston, Jr. (class of 1845), often came from nearby plantations and the prominent families that ran them. Only one mile north of campus, Houston came from Capt. James Houston’s “Mt. Mourne.” The Houston house (today known as the George Houston House) is also close to Rufus Reid’s own “Mt. Mourne Plantation” and George W. Stinson’s (Davidson trustee 1842-47) “Woodlawn.” These three 19th century buildings are all in the National Register of Historic Places.* Incidentally, they are also located in an area that was once the land-grant property of Alexander Osborne and later his son Adlai Osborne, an area or plantation that was known as “Belmont.”

According to the 1800 Iredell Tax List, “Bellmont” was then valued at $1,800, the Houston’s place at $700, and Ephraim Davidson’s at $550. These were the highest valued properties in lower Iredell. Many decades later, the 1860 Iredell County Slave Schedule still recorded these families among the most prominent slaveholders: Isabella Reid (Rufus Reid’s widow) registered the possession of 62 enslaved persons; James Smith Byers (George W. Stinson’s twice father-in-law) registered 54; George W. Stinson himself reportedly had 43 enslaved people at “Woodlawn”; George F. Davidson (Ephraim Davidson’s son, and you guessed correctly: also J. H. Houston’s guardian while a student at Davidson College) registered 50; William Lee Davidson II also appeared in the records with 26.

J. H. Houston’s familial connections did not only grant him much economic and social power in the area, but were in fact, fundamental to the history of Davidson College in one way or another. He was part of Davidson’s Board of Trustees from 1850 to 1856. Observing important sessions as secretary to the board, his name appears, for example, in the minutes of meetings held to accept and manage Maxwell Chamber’s donations to the College. His mother was Sarah Davidson Kerr, whose second husband (they married in 1850) happened to be her cousin William Lee Davidson II, a Davidson trustee from 1836 to 1853. According to the Presbytery Minutes, he sold the initial 469 acres for $1,521 to the institution that would bear his father’s name. Additionally, you might find it interesting that this sale consisted of two tracts, a 269 acre tract referred to as the “Jetton” tract, and a 200 acre tract known as the “Kerr” or “Lynn” tract. Before belonging to W. L. Davidson II, the latter piece of land was in the hands of Alfred D. Kerr, Houston’s uncle.

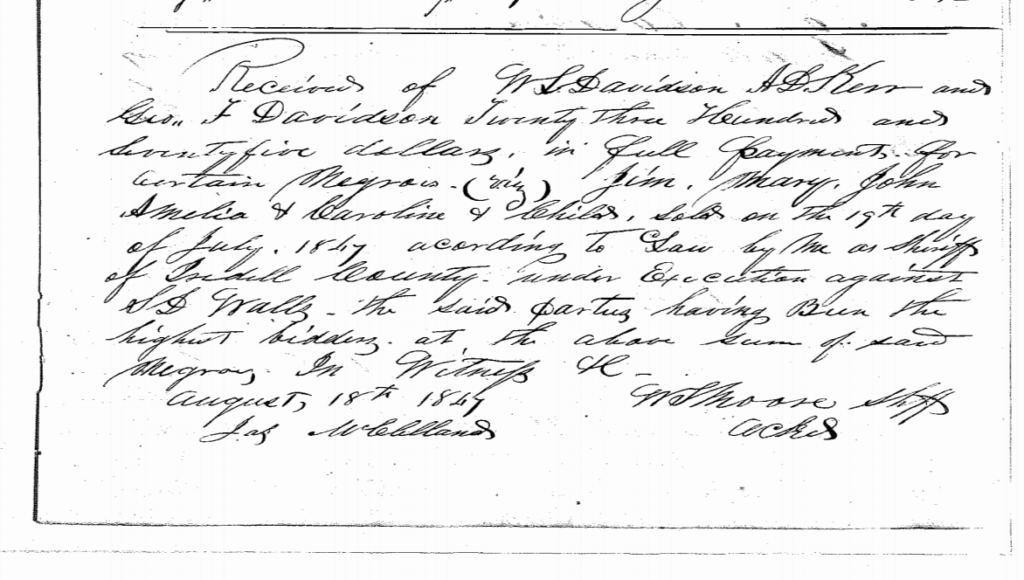

Both W. L. Davidson II and A. D. Kerr appear prominently as “grantors” and “grantees” in the Iredell County “Slave Deeds,” which are property deeds such as bills of sale, deeds of trust, divisions of property that are registered with county courts and that contain information about enslaved individuals (see: People Not Property project). In 1847, for instance, 5 adults named Jim, Mary, John, Amelia, and Caroline, as well as an unnamed child, were bought for $2,375 by W. L. Davidson II, A. D. Kerr, and George F. Davidson (who was also a UNC trustee 1838-1868).[i] In comparison to the great majority of other records, this one stands out for the relatively high amount it represented and the fact that there were 3 different grantees. Could the amount be a hint of the types of skills these 6 people had or the work they would be forced to do? It is also possible that they travelled with W. L. Davidson and Sarah Kerr when they moved to Alabama before 1850.

In 1826, when J. H. Houston’s father died, and with A. D. Kerr as executor, 8 children with the names of Sarah, Betty, Lucy, Phebe, Simon, Debby, Bill, and Molly were all granted to W. L. Davidson II for $10.[ii] Similarly, in 1835, Dick, Mary, Jackson, Jane, Isaac and Ibby, appear in the records as a gift from Alfred Kerr to his sister Sarah and George F. Davidson.[iii] These records tell us almost nothing but the names of these children, who surely had descendants of their own.

Despite the fact that our little fragmented story begins with Dr. J. H. Houston Jr., he fails to be the center of it. On the other hand, what appears to be central from this are the questions it raises about the connections between groups such as early trustees, students, nearby plantations, and the communities within and near Davidson. How was the geography of what we know as “Davidson” different? What type of connections did it foster? Who was able to attend Davidson and in what capacity? Why was it overwhelmingly supported by wealthy slave owners? As our interest and knowledge about the early days of Davidson College increases, maybe similar questions can continue to be our best guide.

Notes and References:

[i] Iredell County, North Carolina, Deed Book X: 463.

[ii] Iredell County, North Carolina, Deed Book M: 314.

[iii] Iredell County, North Carolina, Deed Book R: 150.

*Many thanks to Andy Poore of Mooresville Public Library for access to relevant documents and his extensive knowledge of the area.

More resources: