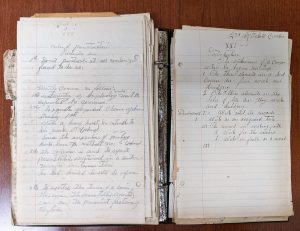

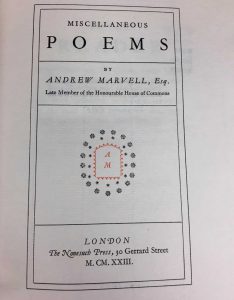

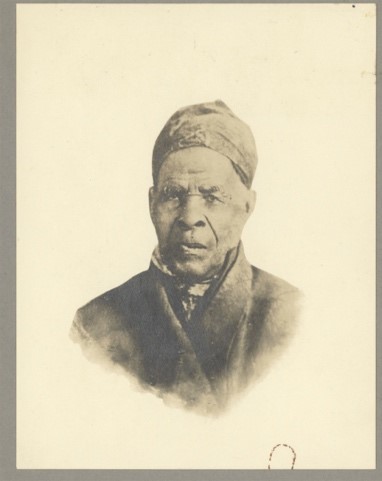

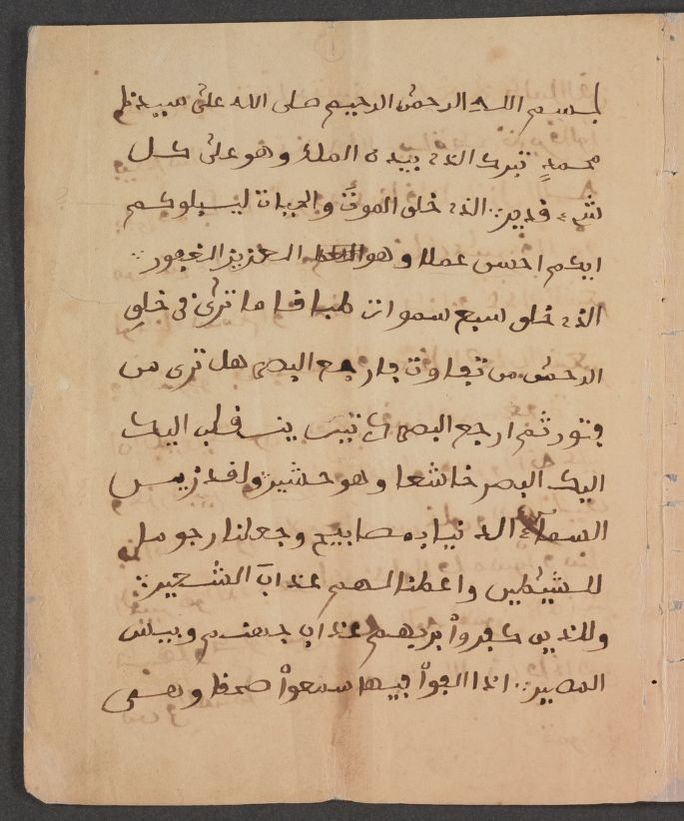

“In the name of Allah, the merciful, the compassionate…”[i] So begins the first sentence of the 1831 autobiography of Omar ibn Sayyid (c. 1770-1863), a man enslaved in North Carolina.[ii] This Arabic-language handwritten manuscript, currently housed at the Library of Congress, is the only known autobiography of an enslaved person that is written in a native African language. At sixteen pages of text, it is the longest document of the fifteen that Sayyid left behind. In it, he details his life in both Futa Toro – the land “between the two rivers”[iii] in what are today Senegal and Mauritania – as well as the United States. The autobiography tells the story of Sayyid’s life, his religious beliefs, and his views on slavery in his own, unfiltered words.

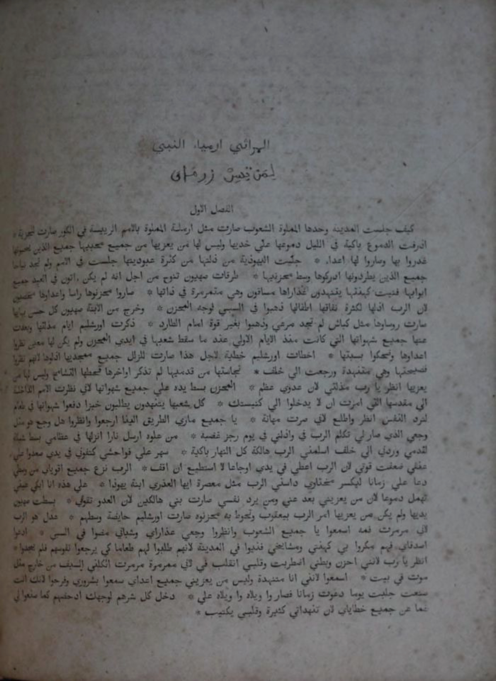

The first page of Sayyid’s autobiography (folio 1a) on which he writes the Qur’anic Surat al-Mulk, beginning with the Basmala. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

This document is only part Sayyid’s rich life story, and it showcases one of the most striking and ubiquitous aspects of Sayyid’s writings: his use of Arabic as a means of resisting his enslavement. In an era when it was illegal for enslaved persons to read and write, not only was Sayyid encouraged to do so by his enslavers, but he also found within the practice a space of personal power to directly question and challenge his captivity.

Sayyid’s autobiography is not the only place he comments on themes of faith and forced servitude. His handwriting also adorns an Arabic-language Bible, currently housed at Davidson College, that he received from his enslavers around 1819. He wrote the Basmala – the same Qur’anic phrase that begins his autobiography – above the Book of Genesis, and his marginalia sprinkled throughout the Bible offers praise to Allah. His notations are most prominent in the Old Testament, where he creates new titles for some of the books by transliterating them into English – a practice that appears in many of the documents he wrote.[iv] Focusing on these books speaks to Sayyid’s interest in how slavery is presented in the Bible, particularly concerning the legal status of enslaved persons, treatment of the enslaved, and manumission.

This opening page of Book of Lamentations shows one of Sayyid’s alternate titles. Rather than the printed “al-Marāthi Irmiyā al-nabi,” (Lamentations of the Prophet Jeremiah) (line 1) Sayyid writes (line 2) “Lmntsn Zrmāy,” an Arabic transliteration of the English “Lamentations of Jeremiah”. (Folio 536, Arabic-language Bible of Omar ibn Sayyid, Courtesy of Davidson College, Archives, Special Collections and Community (DCs 0211-4,5,6))

Sayyid moves further into an examination of enslavement in his own writings. The Qur’anic verse he quotes in his autobiography, Surat al-Mulk (67),[v] can be read as a commentary on his enslavement – and a challenge to it. It asserts that the absolute power of dominion belongs with Allah alone, not man, thus subverting the social power of his enslaver. Neither the slavery of the Qur’an nor the slavery of the Bible, which both include provisions for kind treatment and manumission of the enslaved, align with the brutal race-based chattel slavery Sayyid experienced in the United States.

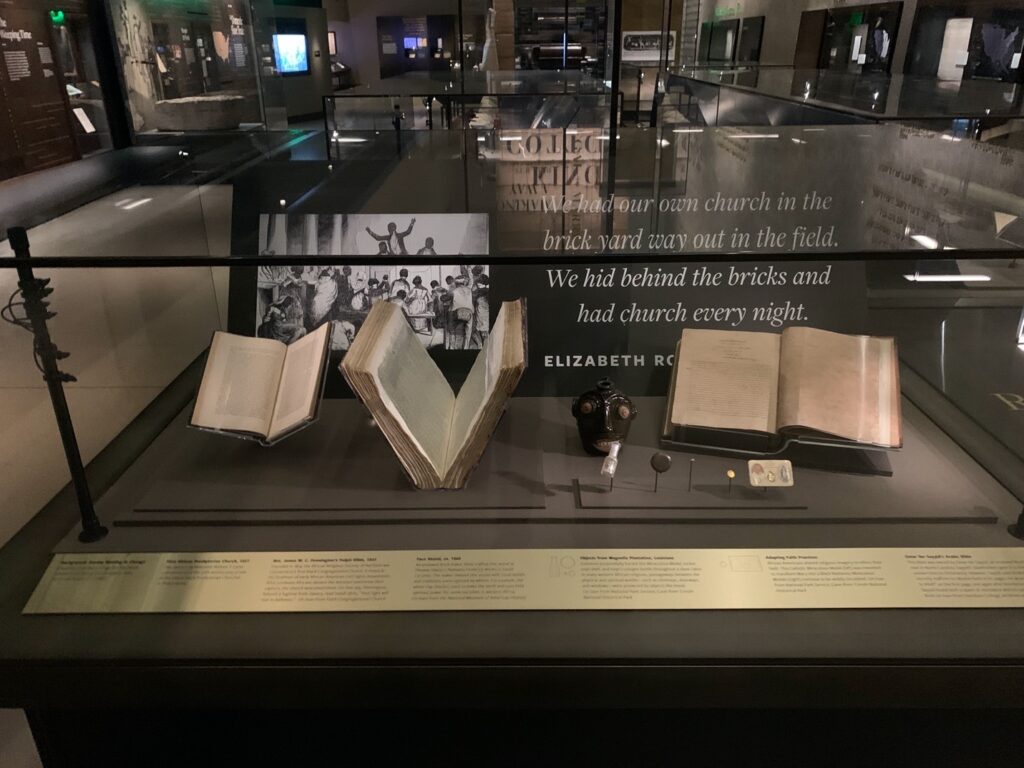

Image of the “Illegal to Preach” case in Slavery and Freedom at the National Museum of African American History and Culture showing Sayyid’s Bible (far right) opened to the final page of Revelations where Sayyid writes “al-hamdu lillah hamdan kathiran” (“Praise be to Allah much praise”). He also includes his name, as well as that of his mother, ‘Umhan Yasnik. (Photograph by John Lutz)

For the first time since Sayyid’s death in 1863, both of these manuscripts are in the same city, Washington, D.C. The autobiography at the Library of Congress, and the Bible on loan to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. One can only assume that Sayyid would appreciate how the work of an enslaved African Muslim resides in the capital of a country that once denied both his humanity and religion – a final act of resistance that writes African Islam into the religious, social, and political fabric of the United States.

*Ayla Amon is a Curatorial Assistant at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and Visiting Lecturer at University of North Carolina Greensboro. She studies African Islam, the African Muslim Diaspora, and the African Muslims forcibly migrated to the United States during the transatlantic slave trade.

**The Sayyid Bible will be on display in the Slavery and Freedom Gallery of the National Museum of African American History and Culture through July 24, 2021.

[i] Called the Basmala, this phrase, “bismillah ir-rahman ir-rahim,” is the first line of the Qur’an and is recited before every chapter (or sura), save the ninth.

[ii] More information on Sayyid’s life, including a page-by-page translation of his autobiography, can be found in Omar ibn Said and Ala Alryyes (trans.), A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar ibn Sayyid (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011).

[iii] Sayyid writes, “bayn al-bahrayn” (folio 14). Omar ibn Said. The life of Omar ben Saeed, called Morro, a Fullah Slave in Fayetteville, N.C. Owned by Governor Owen. Manuscript. 1831. From Library of Congress, Theodore Dwight, Henry Cotheal, Lamine Kebe, and Omar Ibn Said Collection, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018371864/ (accessed January 14, 2021).

[iv] A full exploration of Sayyid’s Biblical marginalia is the topic for another blog post, but some additional examples can be found in Jeffrey Einboden, “Davidson Marginalia,” Northern Illinois University, https://www.niu.edu/arabic-slave-writings/davidson-marginalia/index.shtml, and Allan Austin, African Muslims in Antebellum America: Transatlantic Stories and Spiritual Struggles (Routledge, 1997): 136-137, 140.

[v] The Arabic word “mulk” derives from the tripartite root “malaka” – to own or have dominion over. Sayyid writes the entire sura though he erroneously omits 67:29 and repeats 67:30 twice.