Sara Wilson (she/her) is a senior Anthropology major from outside San Francisco, California. She is interested in osteology, archaeology, and ethical research methods in anthropology.

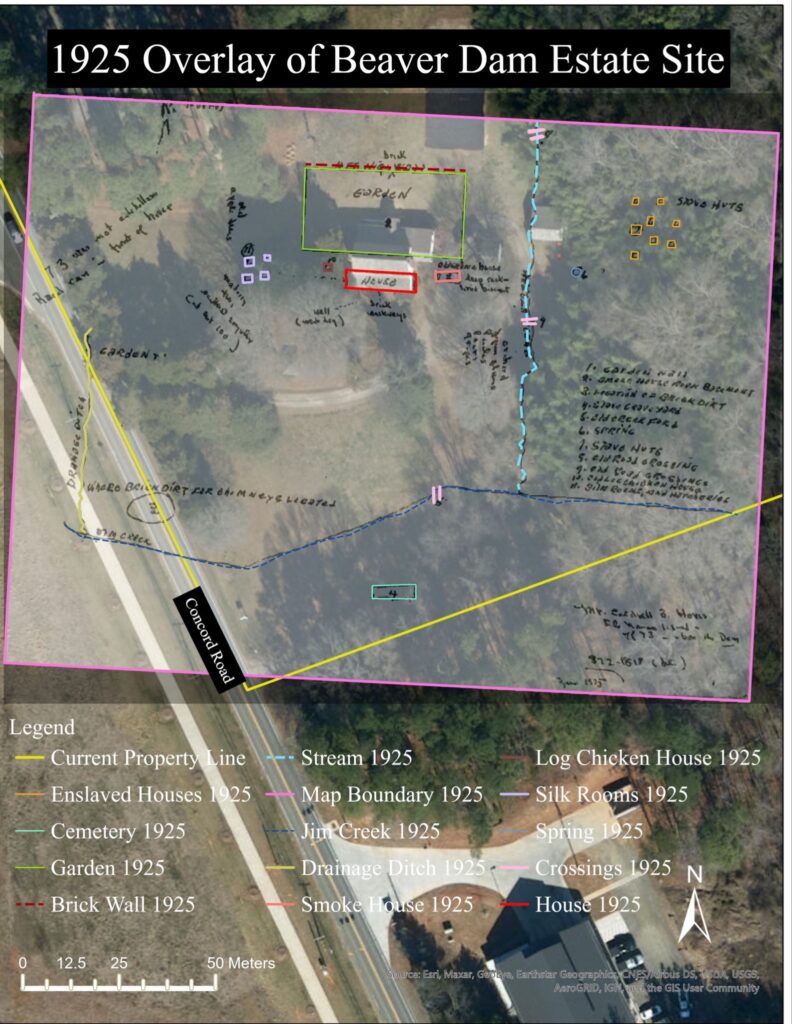

Maps and spatial data increase understanding of the Beaver Dam site during both historical and contemporary times, which lays the groundwork for potential future archaeological investigation. The goal of these maps is to help identify where the houses and cemetery for the enslaved people at Beaver Dam (documented on historical documents) were located. Satellite imagery, LiDAR data, and historical maps were combined in the ArcGIS Pro software to highlight the topography and possible locations of the cemetery and houses. While in-person site survey is integral and yields meaningful discoveries, creating maps is worthwhile as they can reveal patterns, nuances, and spatial relationships that may not be immediately obvious.

As shown by satellite imagery of Beaver Dam, the property is now far smaller than when it was a working plantation, which underscores the possibility that significant features may have been destroyed by neighboring housing developments.

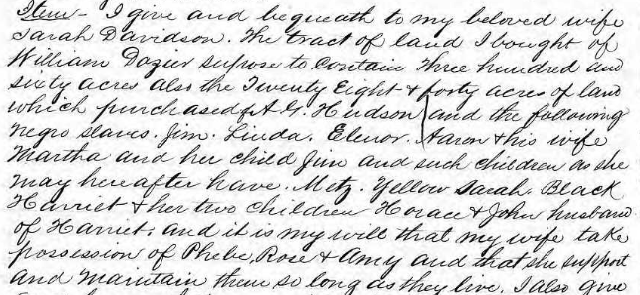

Two historical maps of the Beaver Dam plantation site are sketches from 1865 and 1925. Despite being imprecise, these maps indicate important information that is absent from most historical accounts of Beaver Dam. Both maps included an area for enslaved people’s houses and a cemetery for enslaved people. While the scale of these historical maps is off, analyzing them in conjunction with current satellite imagery and LiDAR data, allowed us to narrow down the potential locations of the houses and cemetery. Topographic raster analyses based on LiDAR data, including hillshade, slope, and elevation contour, reveal a steep incline down to a creek bed along the eastern side of the property. The historical maps position the enslaved houses relative to the main house and to the creek, so having the actual locations of both helps deduce where the remains of the houses may be located. Analyses of the maps indicate that if there ever were houses between the Beaver Dam house and the creek as indicated by the 1865 map, it is likely they are located between the current tree line and west side of the creek.

However, if there was a cluster of houses past the creek as shown in the 1925 map, the River Run housing development was unfortunately likely built on top of it, given the creek marks the eastern boundary of the property. The historical maps indicate that the cemetery was located south-southeast of the main house. This is also supported by topographic data, given that cemeteries are typically located on higher ground. If this project moves forward, the cemetery area should be marked and preserved, and the location of houses could be investigated through archaeological investigations.

This mapping project will have continued utility if the Beaver Dam project proceeds, as geolocating features, artifacts, and other archaeological findings would be a useful visualization technique. These maps are also helpful for working with the community, as they are a way to communicate information that is visually interesting and more accessible.