Originally from Athens, GA, Paul Mullinax ‘22 is an Environmental Studies major and Anthropology minor. He is also a member of Davidson’s Varsity Men’s Track and Field team and in his free time is an avid hiker who spends time outdoors.

Over the last couple years, Davidson College has begun addressing the problematic aspects of its history, particularly its connection to the Davidson family, their plantation, and their ownership of slaves. What’s left of the plantation, referred to as the Beaver Dam Estate, is just a short five-minute drive from Davidson’s campus. During the 2021 spring semester our class, Ethical Archaeological Research, set out to research this plot of land in hopes of uncovering and preserving a story that had yet to be told. In particular, we believe there is strong evidence of a cemetery used by the enslaved people of Beaver Dam, an important discovery that should be preserved. For this reason, it is imperative that we understand the current state, county, and federal laws surrounding historic black cemeteries and what this could mean for Beaver Dam.

As of the writing of this blog post, there is currently no federal law protecting historic African American cemeteries. These cemeteries are often at risk of being destroyed due to development, but a new bill could change that. Just recently the African American Burial Grounds Network Act was unanimously passed by the Senate and is now waiting to be voted on by the House. This bill could implement a network to help coordinate experts and community leaders to help with the preservation of historically significant cemeteries such as the one at Beaver Dam.

Originally proposed in the House in 2019 by Alma Adams, Rep for North Carolina’s 12th District which includes Davidson, the bill initially failed to make headway. This was for a few reasons. For one, the cost of such a program seemed difficult to justify given what other projects already existed. There already exists a National Underground Railroad Network to Free as well as the African American Civil Right Networks. On top of that The Reconstruction Era National Historic Network and a network focusing on the interpretation and commemoration of the Transcontinental Railroad were already in the works to be set up. These concerns were brought to life by the Deputy Director of the DOI and NPs during a subcommittee meeting in May of 2019. They stated that for the reasons of costs and preexisting and similar projects, they would not support the bill, nor the creation of this network. Luckily the Bill was revived, this time in the Senate, by Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio and is progressing much better than its predecessor.

The proposed network would work similarly to the already existing networks previously mentioned, working through the NPS and providing funding for technical support, recording, documentation, and other forms of aid to any project that requests help. This is exactly the kind of help that the Beaver Dam project could benefit from, and with a little luck, it may not be long before we have the resources necessary to proceed with the next steps of this project.

Complementary information may be found here:

https://afro.com/senate-passes-bill-to-create-african-american-burial-grounds-network/

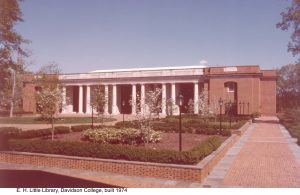

Last Wednesday, Davidson College community members had the unique opportunity to attend a free advanced screening of Bart Layton’s most recent film, the true-crime thriller “American Animals” which was filmed on campus during the spring of 2017!

Last Wednesday, Davidson College community members had the unique opportunity to attend a free advanced screening of Bart Layton’s most recent film, the true-crime thriller “American Animals” which was filmed on campus during the spring of 2017!