On September 18, 1918, the fall term of the 1918-1919 academic year began at Davidson. Three weeks later on October 9, 1918, The Davidsonian reported that the college experienced “a severe visitation” of Spanish influenza. From the report of the first case, new cases began to emerge rapidly. The infirmary, although equipped with medical equipment and staff, quickly became overrun with patients. To more adequately attend to the sick, the Chambers building, the main academic building on campus (which also had two wings set aside as dormitories), was turned into a makeshift hospital. At first, only the first floor of the south wing was used to house the sick. However, cases continued to appear and the second and third floors of the wing were quickly repurposed as hospital wards (“‘Flu’ Epidemic Takes Heavy Toll at Davidson”).

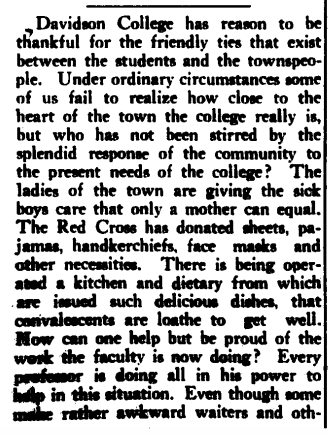

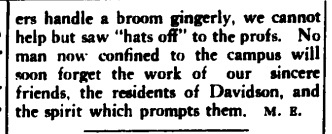

With an ever-increasing volume of cases, campus administration decided to suspend class for three weeks and to place campus under quarantine. To care for the sick, the entire Davidson community offered support. Nurses attended to the ill, the women of the Davidson Red Cross Chapter provided meals and necessary supplies, and Davidson professors took regular shifts to assist in any way they could. One individual, presumably a student (and possibly one of those infirmed) remarked about this extraordinary support offered by the community in the October 9, 1918 Davidsonian (“Editorial”).

These combined efforts worked. Remarkably, the next issue of The Davidsonian (October 23, 1918), reported that after three weeks of cases of the Spanish flu on campus, the epidemic was practically over. In total, over 200 cases of the flu were reported and those remaining were rapidly recovering (“‘Flue’ Has Vanished From Davidson College”). However, one student, Daniel J. Currie of Defuniac Springs, Florida, did pass away from pneumonia, which was likely resultant from the influenza. Nurse Laura Rose Stevenson of Charlotte treated patients at Davidson and also died of pneumonia (“In Memoriam”).

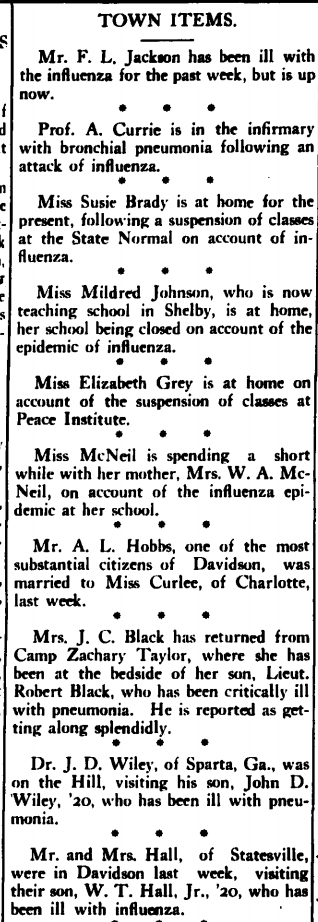

While the college was rocked by the flu, the Town of Davidson was as well. The sick were treated in their homes, cotton mills and schools temporarily shut down, and the town was placed under quarantine. The October 23, 1918 issue of The Davidsonian included notices of townspeople affected by the influenza (“Town Items”).

Like in the case of the college, the Red Cross provided assistance to the Town of Davidson. In total, over 150 cases were reported in the town. There were at least five deaths from pneumonia, most of which were African American (“‘Flu’ Situation in Town Is Now Much Improved”). The next week, in the November 6, 1918 Davidsonian, it is reported that the town’s quarantine had been lifted and that mills had resumed work (“‘Flu Situation In Town Continues to Improve).

Although the events of the Spanish flu epidemic occurred over 100 years ago, we find ourselves in a very similar situation today with COVID-19. What can we learn by reflecting on Davidson’s response to the Spanish flu?

I think it is this: It takes all of us to get through it. In 1918, this was evident in medical personnel, townspeople, and the college community coming together to help one another. In 2020, we can see the same thing occurring. We are helping each other by tending to the ill, by donating supplies, by abiding stay-at-home orders, by offering each other emotional support. The list goes on and on. We are all trying our best to help each other get through it. And I think that is worth everything.

As Davidson adjusts to the COVID-19 pandemic, we are challenged to develop new ways to engage and interact with our community. Davidson College Archives, Special Collections & Community, which regularly collects, shares, and preserves the college’s and community’s unique stories, would like to document the experiences of students, faculty, staff, alumni, and community members during these uncertain times. To this end, we are excited to present our initiative “(Re)Collecting COVID-19: Davidson Stories.” In this crowdsourcing project, we invite you to share your COVID-19 story through the contribution of original words, music, video, art, or images, regardless of whether you are on campus, in the Town of Davidson, or thousands of miles away. To learn more about “(Re)Collecting COVID-19: Davidson Stories,” please visit the site.

Works Cited

“Editorial.” The Davidsonian, [Davidson, NC], 9 Oct. 1918, p. 2, library.davidson.edu/archives/davidsonian/PDFs/19181009.pdf.

“‘Flu’ Epidemic Takes Heavy Toll at Davidson.” The Davidsonian, [Davidson, NC], 9 Oct. 1918, p. 1, library.davidson.edu/archives/davidsonian/PDFs/19181009.pdf.

“‘Flu’ Situation In Town Continues to Improve.” The Davidsonian, [Davidson, NC], 6 Nov. 1918, p. 1, library.davidson.edu/archives/davidsonian/PDFs/19181106.pdf.

“‘Flu’ Situation in Town Is Now Much Improved.” The Davidsonian, [Davidson, NC], 30 Oct. 1918, p. 1, library.davidson.edu/archives/davidsonian/PDFs/19181030.pdf.

“‘Flue’ Has Vanished From Davidson College.” The Davidsonian, [Davidson, NC], 23 Oct. 1918, p. 1, library.davidson.edu/archives/davidsonian/PDFs/19181023.pdf.

“In Memoriam.” The Davidsonian, [Davidson, NC], 23 Oct. 1918, p. 2, library.davidson.edu/archives/davidsonian/PDFs/19181023.pdf.