I was hired as the Justice, Equality, Community (JEC) Project Archivist as part of the campus-wide Justice, Equality, Community (JEC) grant initiative at Davidson College in August 2017. The 3.5 year JEC grant aimed to “reimagine humanities curricula through the lens of three ideas that cut across cultures, time, and disciplines: justice, equality, and community…to demonstrate the critical role of humanistic inquiry in public discourse, global problem-solving, engaged citizenship, and democratic leadership.”

To accomplish these lofty goals, the initiative included funding for research partnerships between faculty and students, a series of practitioner-in-residences, community-minded experiential learning projects, and archival collecting and digitization efforts centered on questions about race and religion in the greater-Davidson area. As the JEC Project Archivist, I was responsible for the following tasks in support of the grant’s archival component:

- Identifying and digitizing JEC collections.

- Integrating JEC materials into at least 5 new courses.

- Expanding archival collections related to JEC.

- Leading public programming about JEC materials, both on campus and in the larger community.

Let’s take a look at how we faired with these four goals and the work that remains. In the last three years, we have digitized:

- over three dozen oral histories,

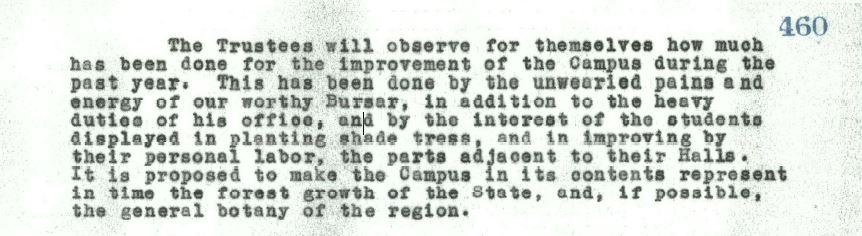

- the 19th century faculty minutes and trustee minutes Davidson College, as well as the nineteenth century Davidson College Presbyterian Church minutes,

- the 20th century faculty minutes of Davidson College,

- the records of the Davidson, NC Community Relations Committee,

- the records the Black Student Coalition,

- the Arabic Bible of Omar ibn Sayyid (now on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture)

- relevant selections from the Davidson College Chaplain’s Office Record Group,

- materials from the Chalmers Gaston Davidson Plantation Files collection,

- and our latest, “coming soon” addition: the complete runs of the Davidson Monthly and Davidson Journal.

We incorporated these digitized materials into at least two dozen course sessions, outreach programs like “An Evening with…” and multiple presentations to local historical societies. The collections were also used to support some of the research efforts of the Davidson College Commission on Race and Slavery. We then used the student work collections as examples when speaking to student activists and leaders about the importance of saving their records and establishing dialogues to help us learn how to more equitably and respectfully do that work through the JEC Student and Alumni Advisory Council.

These class sessions and outreach initiatives led to several multi-year course collaborations that resulted in donations to the archives in some cases and high-profile projects in others. For example, the hard work of Dr. Jane Mangan’s HIS 259: Latinos in the United States course resulted in nearly two dozen oral history interviews documenting the Latinx experience of Davidson (now viewable, here). Another oft cited project is Disorienting Davidson, a multi-year student-led project that informed the senior thesis work of H.D. Mellin ’20. Mellin utilized many of the collections later made digitally available by JEC grant funds over the course of several semesters for this groundbreaking student project. Their work also helped archivists identify highly sought-after collections that informed the digitization selection process.

While collaborations within the department and across teams have led to significant strides in terms of access to archival collections and course collaborations, much work remains in terms of community outreach and collections development around the issues of justice, equality, and community. In recognition of that need, the Justice, Equality, Community Archivist position was made permanent at Davidson College in March 2021.

To access the digitized collections mentioned in this blog post, please email archives@davidson.edu.

Related Posts:

- Digitization Projects: Community Change and Oral Histories, Part 1

- Digitization Projects: Community Change and Oral Histories, Part 2

- Justice, Equality, Community (JEC) Student and Alumni Advisory Council

- The Davidson College Task Force on Racial and Ethnic Concerns, 1984

- Justice, Equality, and Community Archivist Is In The Library!

![Interviewer: How did you end up at the Sunday school [at the mill chapel]?

Margaret Potts: Well I was teaching Sunday school in Davidson Presbyterian Church, early. They wanted me to have the little ones, the two in, whatever hours it was, babysitting more than anything else, in the old church. It was a terrible place to have little children. But anyway, so just through the years, I would teach Sunday school and do things like that, whatever needed to be done. And so, some of the students, some real good students here at Davidson took on the mill project. And they got anybody that they could get to go and help there. And of course, I knew a lot of the people over there, so I was willing to help. (laughter) And until I went off to go to college, and then I had to stop doing that. [Page 26]](https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/aroundthed/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/05/transcript_audio154_potts.jpg)

![Margaret Potts: Well, I liked the track meets; oh I loved the track meets. I didn’t miss a single one of those. And in the summertime, we used to come out, and [00:49:00] they would let us -- not complain, if we played. We never did anything terrible. But on this very spot, right here, where this library is, they had this tremendous jungle gym for adults. And what, where they got that, I don’t know whose idea it was to put that thing together. It was metal, big metal things, put together, and it had a ladder that went up two stories and it went all the way across. Now this is was when I was a child. It had -- was hanging down, and a place for you to sit, and you could swing back and forth. It had the most interesting jungle gym I’ve ever seen. They let us play on that. We used to spend hours over here. I think the -- [00:50:00] what was behind? The gym was behind it. And it was in front of the gym.](https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/aroundthed/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/05/transcript_audio154_potts2.jpg)

![Interviewer: I know. Asking about, or mentioning Carl reminds me, do you remember a fire in 1949 in Brady’s Alley, (inaudible) –

Mildred Thompson: Oh, yeah, I sure do. I remember that like it was yesterday. Carl was the minister, and Carl was the one that, I’m not positive about this, but I’m pretty sure, he’s the one that started that children’s sermon before church, you know, that called the children down. I think he started that, because I can remember him seeing him come down out of the pulpit, and the little children would just listen, and they’d turn around and say to their parents, “Is that true? Is that true?” When Carl was telling the story.

But anyway, about that, it was almost time for church to be over, and this fire started, and the fire was just blowing, blowing. And of course, everybody was apprehensive, “Where is it?” Well anyway, it was down in that alley; that was pathetic. Those people, I don’t know where they had water, I don’t know what they had, but what they had was pretty bad. And so Carl, after that he went down there and he investigated everything, and he told, he got in the church, and he said, “I refuse to preach in a church where the shadow of the church falls on poverty.” Honey, that afternoon, he took the young people around, it was terrible. Honey, he really turned this place around. [Page 9 -10]](https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/aroundthed/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/05/transcript_audio159_thompson.jpg)

![Patricia Sailstad: And I remember the first time we ever had an integrated World Day of Prayer, and I went with Ms. Maude, and it was over at the little Methodist Church that has the log cabin next to it. Oh, gosh. Well, it’s…this is not the black church there. This is the one behind it. It was a white church at the time. But they decided they would have refreshments.

And actually, this was... But it was the first time they’d had black and white together, and after the ceremony we went to their little log cabin, which was right next to it. You’ll see the church; it’s a Methodist church, I think. Now it is a [00:40:00] black church, but it was white at the time. And so there we were (inaudible) standing up. We weren’t sitting down, eating. And Ms. Maude said, “You know, Mrs. Sailstad.” She looked around at the black and the white together, all chatting. She said, “I think this is what heaven must be like.” [Pages 23 – 24]](https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/aroundthed/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/05/transcript_audio107_sailstad.jpg)

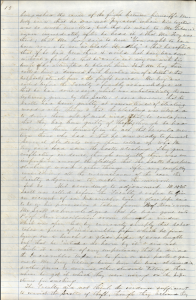

![¬¬Dolly Hicks: At one time we had a union that picketed, trying to get the union in at the old Davidson Cotton Mill…I remember from down the street cars just -- But we weren’t allowed up there because there was trouble going on up there -- Up at the mill, so you can see it from right where -- back then it looked like a hundred miles, but it’s only, [00:30:00] what, not very far at all, half a block. (laughs) But they did have some over there. Now, [Beatrice?] might could tell you more about that -- but I remember it very distinctly, because we were not very young at that point…’cause I was born in ’25. It would probably be in the early ’30s…But the union or something came in, something they were doing up there, and there was cars, and seems like somebody got hurt.

E.M. Hicks: They had the flying [00:31:00] squadron. Had a flying squadron came out of the North, and they were coming down through the South, and they were going to organize the South. And so they came through Greensboro. Now, this would have been the ’30s. And they came through Greensboro, because Cone Mills was in Greensboro, and we were out -- I lived close to Cone Mills. And this flying squadron came down there, and I remember very well -- you know, it was different back in those days. I was freer to get out and go where I wanted to than most kids my age. And so I wanted to see what was going on. I went out to Cone Mills, [00:32:00] and I could walk out there easily. And I got out there, and the cops wouldn’t let me -- get close. They kept me back. But in those days the cops wore leather leggings. And so these people who were fighting the cops, some of them were the employees, see, and the others were imports, and they’d take an apple and stick a razor blade down in it, you know, and then if you take your fingers and put it on the wrong side of the razor blade so it would be [toward it?], and throw that thing, and when it would hit these guys on the legs, it cut their [00:33:00] leggings. It cut their leggings. It was rough. I mean, it was kind of tough. But anyhow, the cops won, and they left Greensboro, came on down this way. They got to Gastonia. That’s where the big one was. You can find that on the record, because they had machine guns up on the buildings, and they were sitting up there with machine guns. [Pages 66 – 70]](https://davidsonarchivesandspecialcollections.org/aroundthed/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/05/transcript_audio150_hicks.jpg)