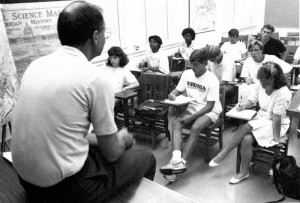

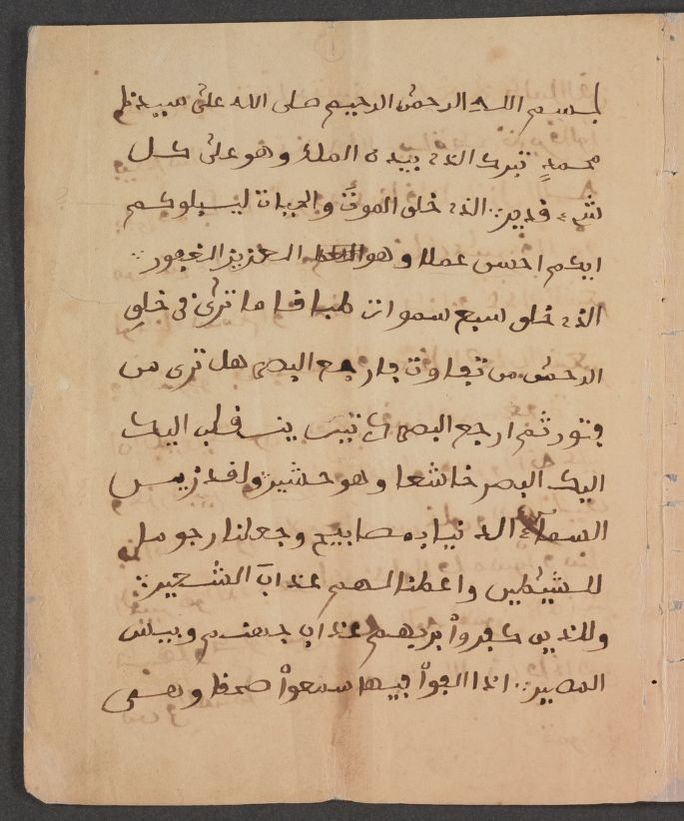

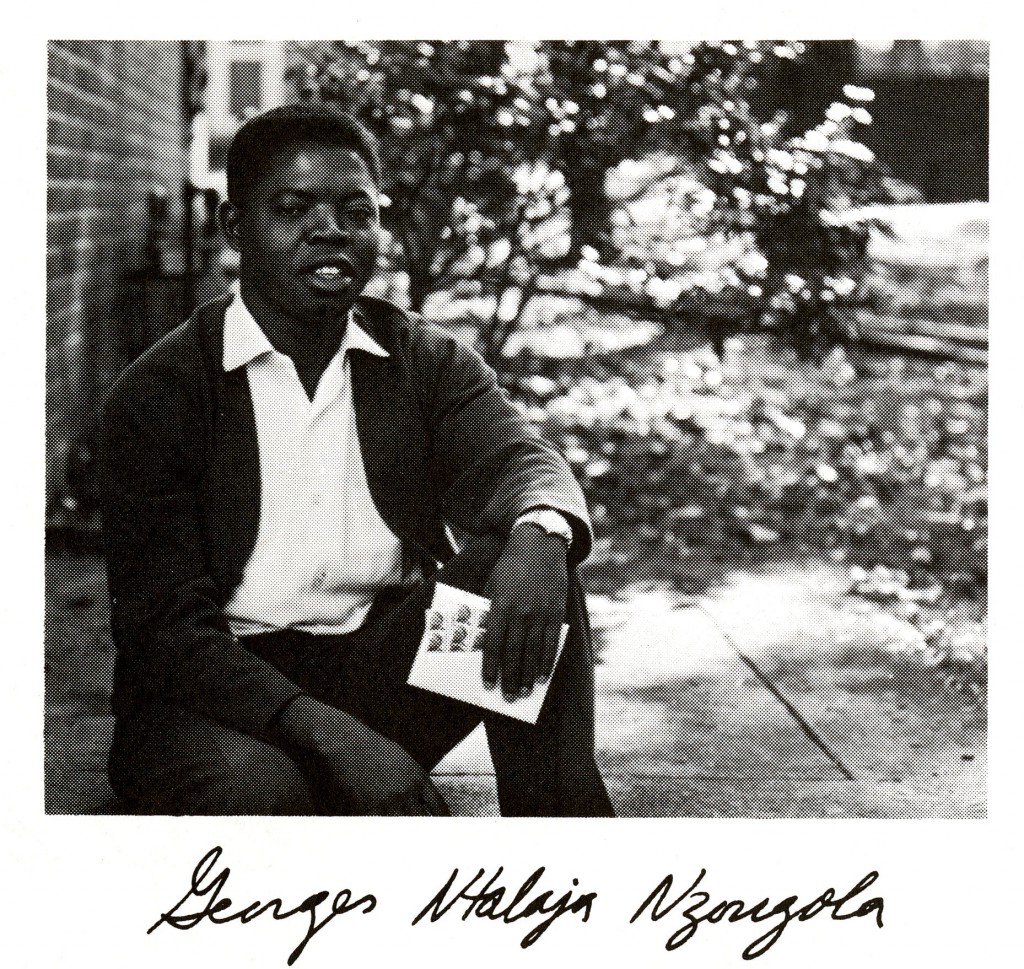

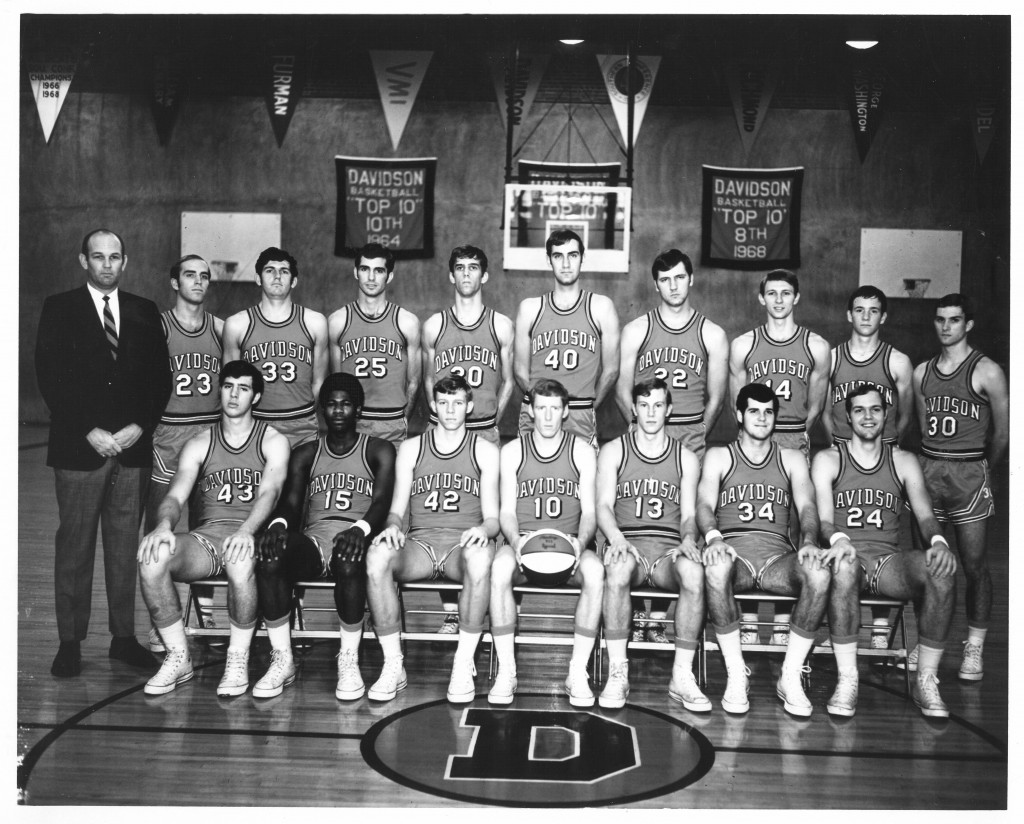

The Sparrow’s Nest, unknown year.

This past July, although activity had slowed down around campus for the summer, a renovation crew discovered that there was much of interest below ground. Specifically, beneath the Sparrow’s Nest. At first glance, the Sparrow’s Nest does not look like much. It is a small, brick cottage nestled between Belk Hall and Vail Commons, across from the Lula Bell Houston Laundry. During the school year, any glimpse of activity in or around the building. To the untrained eye, the Sparrow’s Nest appears to be unused, perhaps simply a storage room. However, the history of the Sparrow’s Nest reveals there is much to be learned about its history with reference to Davidson College and the town of Davidson itself.

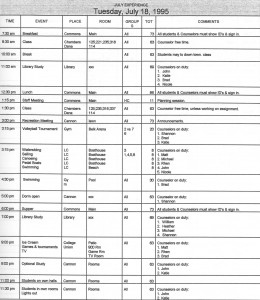

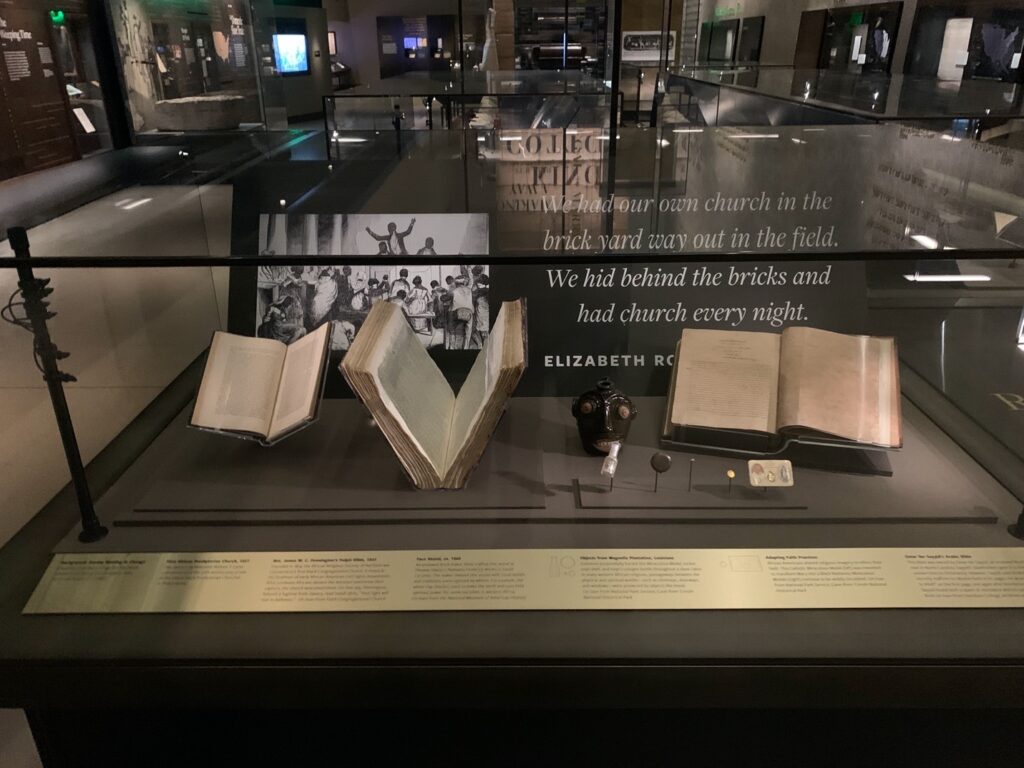

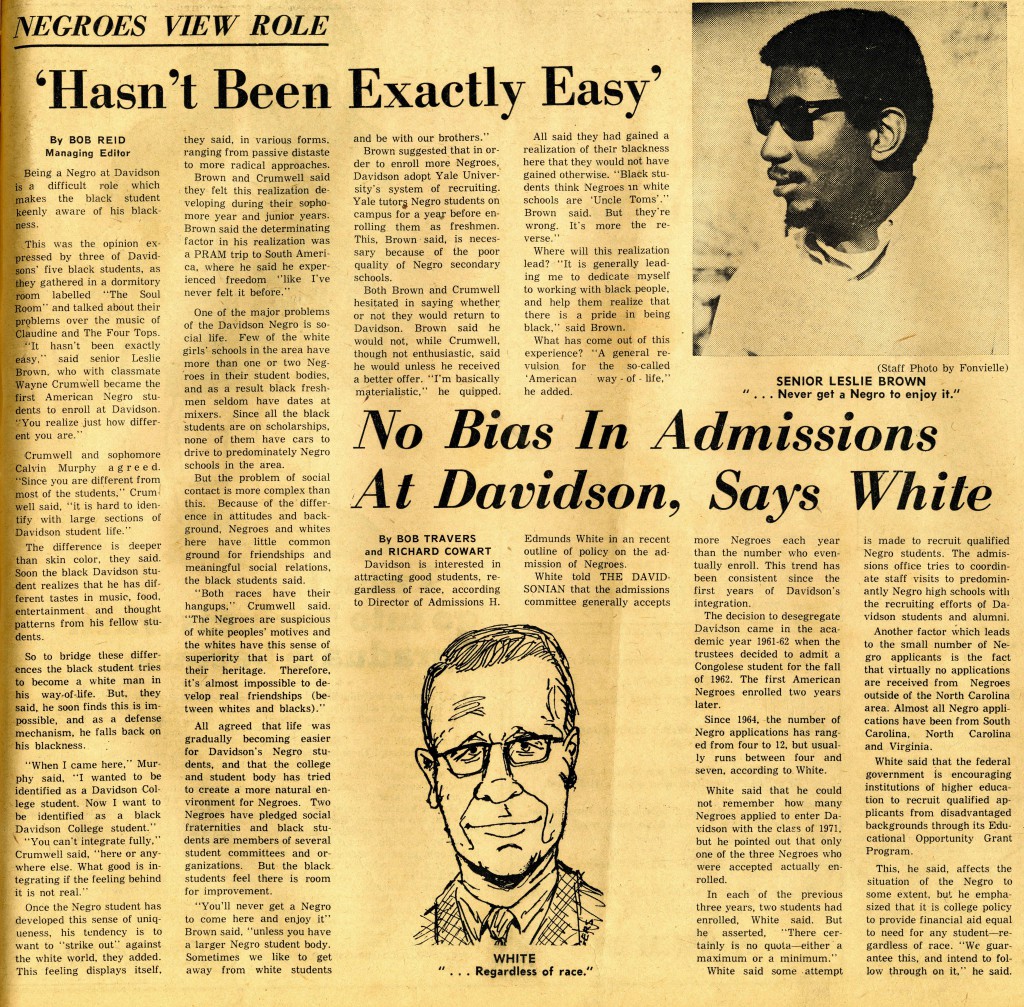

During renovations in July, Barbara Benson, Director of Building Services, and David Holthouser, Director of Facilities and Engineering, informed the College Archives & Special Collections that the crew found more than the expected decay of an old building. Whilst removing the termite-damaged floor system, the renovation crew from Physical Plant discovered a myriad of artifacts from former inhabitants of the Sparrow’s Nest. Currently, the building is used as a Physical Plant facility. Prior, the Sparrow’s Nest served as a Campus Security Office from 1974 to 1990. It was acquired by the College in 1908 and continued to serve as a boarding house for some time after its acquisition.

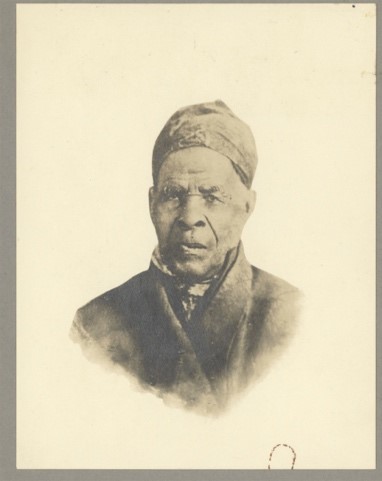

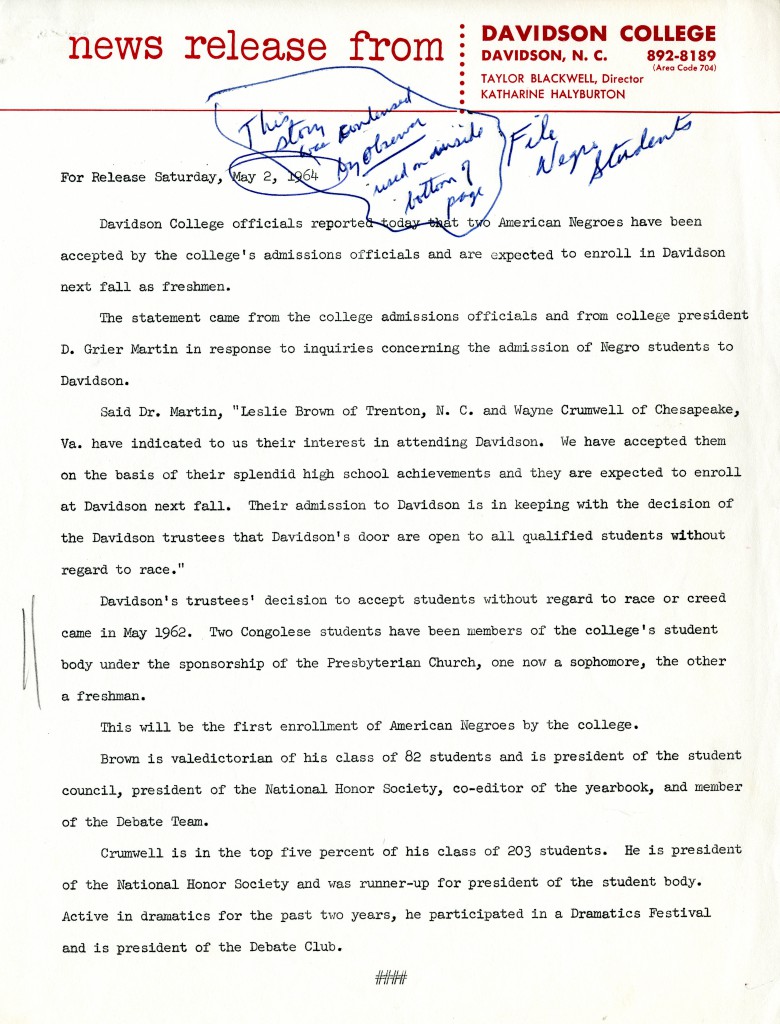

Reverend Patrick Jones Sparrow.

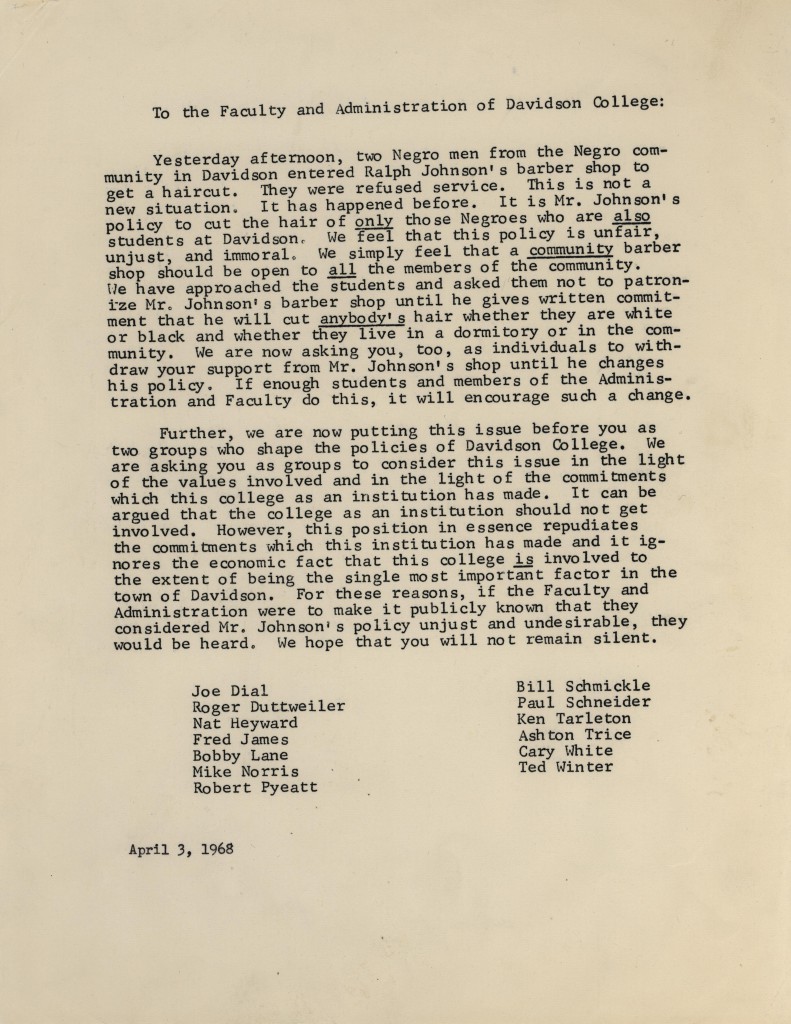

The shoes, animal bones, glass, pottery and personal belongings found beneath the floor of the Sparrow’s Nest in July.

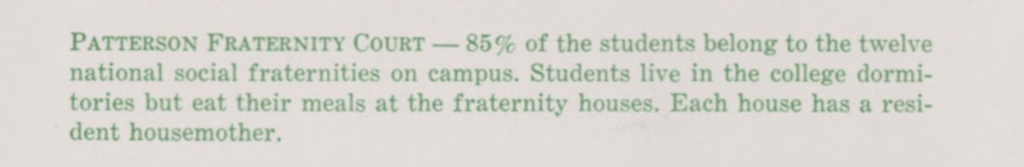

According to The Davidsonian, the house originally served as slave/servants’ quarters for Thomas Williams Sparrow (1814-1890.) Thomas was brother to College co-founder Patrick Jones Sparrow, who taught Ancient Languages at the College from 1837 to 1840. Thomas W. Sparrow married Martha Lucinda Stewart (1820-1905) and together the two ran a boarding house for the college students in a house on North Main Street. In the May 1912 edition of D.C. Magazine entitled “Memories of the Fifties,” J.J. Stringfellow from the Class of 1850 recalls that the Sparrows were nicknamed “Uncle Tom” and “Aunt Tom” by students. Stringfellow describes them as “always kind in treatment and generous at table” and continues to compliment their hospitality saying, “No boy of that olden time can ever forget their famous molasses pies.” Thomas Sparrow is buried in the Davidson College cemetery.

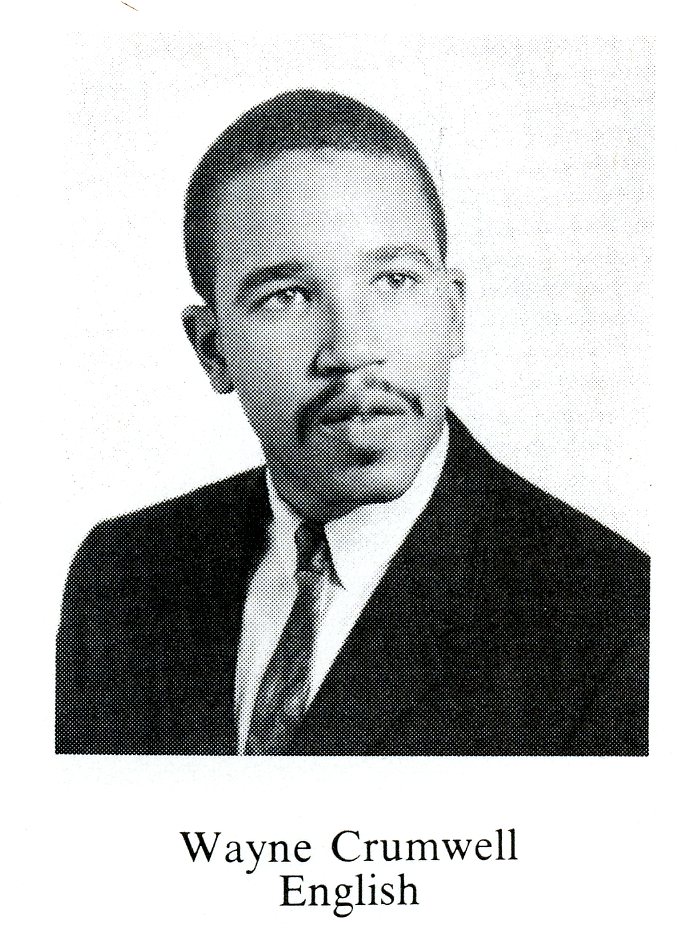

As for the children of Thomas and Martha Sparrow, their daughter Helen married J. Wilson McKay, D.D. from the Class of 1870. He went on to be the president of the Board of Trustees for some time. Their son, John Sparrow (1845- October 30, 1883) was a bit of a troublemaker and was eventually expelled from Davidson College. In 1866, John Sparrow eloped with Helen Kirkpatrick (1847-1900), the daughter of the College President of the time, John Lycan Kirkpatrick. John and Nellie had seven children. Their four daughters were named Anna, Marry, Mattie, and Nellie; the latter married Wilson McKay, the son of Dr. McKay who had been President of the Board of Trustees. John and Nellie also had three sons: Robert Gordon, Thomas Hill, and John Kirkpatrick Sparrow. Although Thomas Hill Sparrow did not attend college at all, his two brothers did. John Kirkpatrick Sparrow was a member of the Davidson Class of 1901 but did not graduate. Notably, Robert Gordon Sparrow was the Valedictorian of the Class of 1888 and long-held the record for the highest grades ever received at Davidson College.

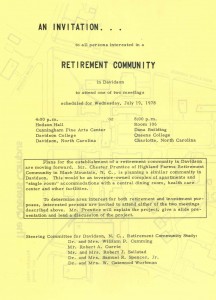

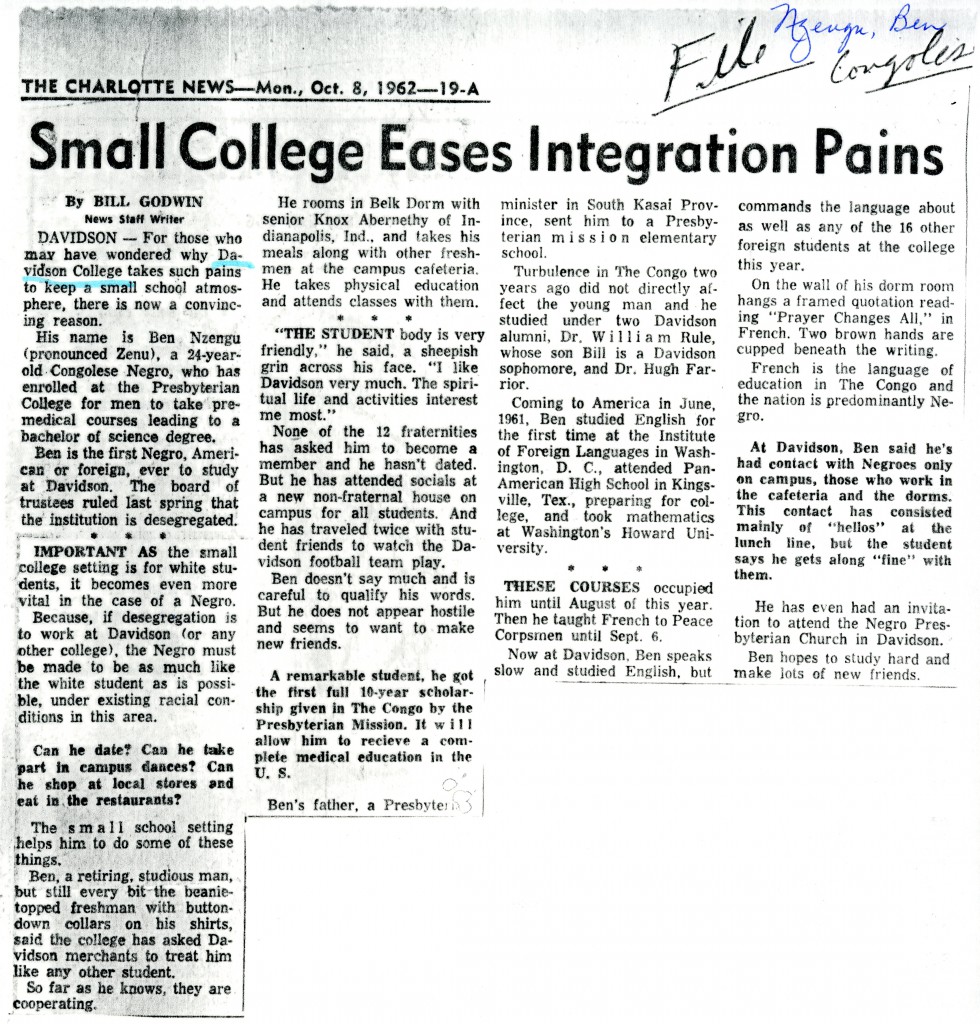

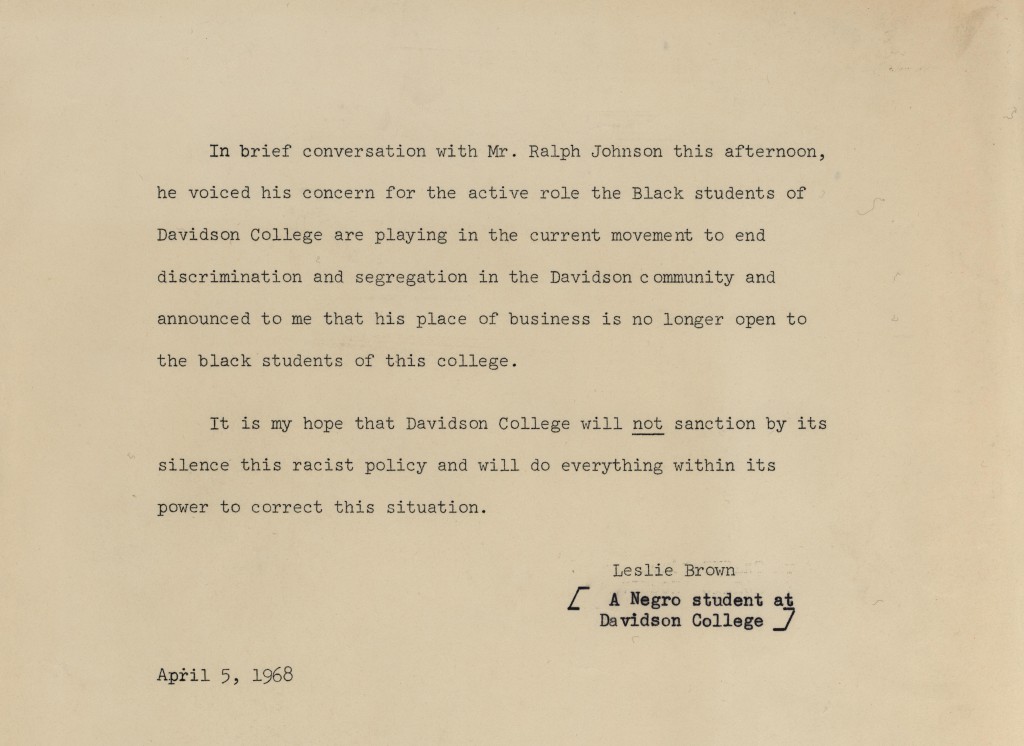

The Class of 1888. Robert Sparrow is pictured second from the left, seated in the first row.

There is great evidence of the Sparrows’ enslaving practices. In an essay entitled “My Unreconstructed Grandmother” by Mary Sparrow Harrison, she describes the attitudes and experiences of her grandmother, Martha Lucinda Stewart Sparrow. Mary remembers Martha as a distant, unaffectionate grandmother who was proud, yet hardened by her Southern heritage. According to Mary, Lincoln’s name was never mentioned in their household but that former enslaved people continued to visit her grandparents annually for years after the Southern “surrender.” Following the death of John Kirkpatrick Sparrow, Mary’s father, a former enslaved person, traveled from South Carolina to grieve with “Miss Martha.” According to Mary, he had been a wedding gift from College President John Lycan Kirkpatrick to Martha. Mary writes that the older gentleman had accompanied her father during childhood, young-adulthood and even when he joined the army in 1862. Of the relationship between this man and her family, Mary writes, ” I do not know how long he stayed with the family after the end of the war or where he went or how he knew that “Miss Martha” need him that day, but I do know that the meeting between those two—the proud reserved women and the ex-slave and friend who had learned of her sorrow and had come to comfort her left an indelible impression on my child-mind.” Perhaps the artifacts discovered beneath the Sparrow’s Nest holds answers as to that gentleman’s identity and his experiences being enslaved and freed by the Kirkpatrick-Sparrow family. In order to continue following the story of the Sparrow’s Nest’s purpose throughout the centuries, follow the blog-tag: “Sparrow” or the hashtag: “DavidsonHistoryMystery” on Instagram and Twitter.